Jamie Noerpel / Witnessing York

Jamie Noerpel / Witnessing York

Jamie Noerpel / Witnessing York

For more than a hundred years, people who were too poor to afford a burial were buried in the York City Cemetery, also known as “Potter’s Field.”

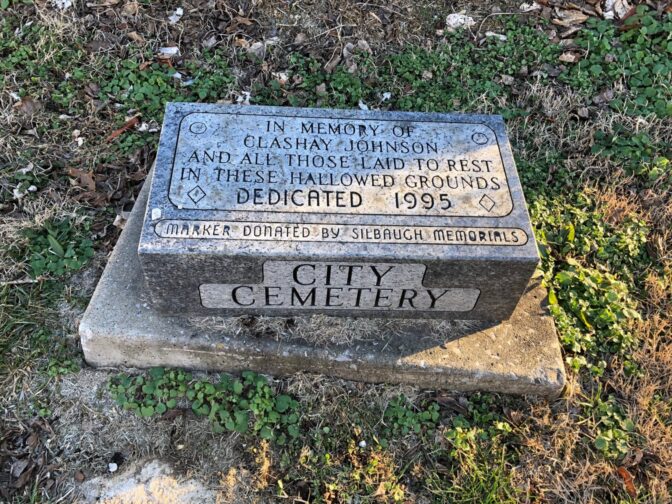

The site along Schley Alley and West 7th Avenue in North York holds the remains of 800 people, most of whom do not have grave markers. The only grave that has a marker belongs to Clashay Johnson — a 15-month-old boy who died in 1987.

A grassroots effort called Project Penny Heaven is trying to raise $20,000 for a monument to honor the names of people interred in the potter’s field. So far, the group has raised $12,770.

Jamie Noerpel / Witnessing York

The only grave that has a marker at City Cemetery belongs to a little boy who died in 1987. A group of college students dedicated the marker in 1995.

Joy Giguere, an Associate Professor of History at Penn State and a member of the Pennsylvania Chapter of the Association of Gravestone Studies, says York’s potter’s field is unusual because it is still there.

“There are, compared to other cemeteries, few Potter fields that have survived the ravages of time and urban development, ” Giguere said. “This is a way to bring in often forgotten elements of the past and of the historical cultural landscape into the public view, so that people can acknowledge the existence of potter’s fields and learn about the types of burial spaces and the treatment of the marginalized dead.”

The history of potter’s fields stretches back to the Middle Ages. In the context of colonial American history, a potter’s field was the place to bury the poor, the unnamed and people of color, Giguere said.

The York project is spearheaded by Jamie Noerpel, a history teacher at Milton Hershey School. Volunteers from Friends of Lebanon Cemetery, as well as Giguere, are also collaborating. Noerpel has been working to create awareness about the forgotten graves of Yorkers through her blog “Witnessing York.”

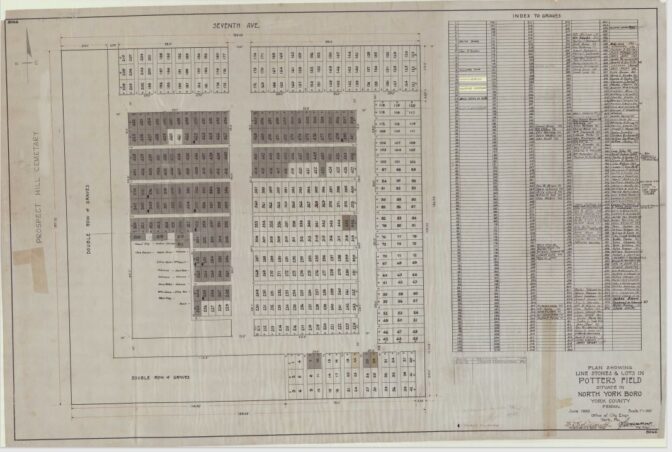

In 1897, York City exhumed the graves of around 600 people who were buried in an old location at West College Avenue between South Beaver Street and South Cherry Lane to a new location next to Prospect Hill Cemetery along Schley Alley — the current site. The city began keeping records at the new site, but there are no records of those unmarked prior to the move. Project Penny Heaven’s team knows the names of about 225 people buried there thanks to city records compiled in the 1930’s that show evidence of graves as old as 1873.

Michael Shanabrook / City of York

A grave index of York City Cemetery from 1930.

In 1974, York changed the cemetery’s name from Potter’s Field to York City Cemetery, said Michael Shanabrook, who has worked as an archivist for York City for 45 years.

The site is widely known as the place where the city would bury the poor, the unnamed and people of color. Samantha Dorm — a volunteer for Friends of Lebanon Cemetery — says there is evidence the site functioned primarily as a Black cemetery before the city moved its location in the late 1800s. In her research, Dorm found a map from 1850 that identifies part of the site as a “colored cemetery.” She believes many of the unidentified people who are in York City Cemetery are African-American.

“When you look at the list of known names, I think it’s maybe 124 white, 94 black and then other, but I know that that number is much higher for the Black community, because it was the colored cemetery, but there’s no documentation of who those folks were that were in that ground from 1850,” Dorm said.

From the list of known names of people buried in York City Cemetery, about 44% are people of color, Giguere said.

Shanabrook says he personally avoids using the term “indigent” to refer to the people buried in York’s potter’s field. He said some of the people there might have been transient visitors.

“If there was a businessman that came to York, and he died, and they can’t reach your family, they don’t know what religion he is. He could be a very wealthy businessman or farmer, or worker, he’s going to be buried in a potter’s field because they don’t know what to do with them,” Shanabrook said.

In the meantime, the group is working to put a face and a story to the people known to be in the York cemetery. The team is conducting genealogical research to identify any living relatives of people buried at the site and organizing educational events for the community.

The days of journalism’s one-way street of simply producing stories for the public have long been over. Now, it’s time to find better ways to interact with you and ensure we meet your high standards of what a credible media organization should be.