Derry Township School District psychologist Jason Pedersen, left, and Superintendent Stacy Winslow, right, stand in the hallway at Hershey Middle School.

Brett Sholtis / Transforming Health

Derry Township School District psychologist Jason Pedersen, left, and Superintendent Stacy Winslow, right, stand in the hallway at Hershey Middle School.

Brett Sholtis / Transforming Health

Brett Sholtis / Transforming Health

Derry Township School District psychologist Jason Pedersen, left, and Superintendent Stacy Winslow, right, stand in the hallway at Hershey Middle School.

(Derry Township) — It was just after noon when the eighth graders at Hershey Middle School burst out of their classrooms and filled the halls. The 200 or so students talked, laughed and joked around as they headed to the cafeteria, their brisk paces slowed only by teachers who reminded them not to run.

These sounds were a joy for elementary and middle school psychologist Jason Pederson. He said last year, when the school was limiting how many students could be in the building at once, it was “almost eerie” to walk the silent halls and glance into the sparsely-populated rooms. Now, students are getting the full experience—both in class and in their social lives.

“Their peers are here,” Pedersen said. “Obviously everybody would love not to be wearing masks. However, it’s not a reality in the moment.”

Standing next to him, Derry Township School District Superintendent Stacy Winslow said wearing face coverings has not been an issue for the roughly 875 students at the middle school. Fewer than five special needs students have required accommodations, which the school provided, such as a different type of covering and the option to take breaks from wearing it in a designated location.

“The kids have been great about it,” Winslow said. “I know a lot of parents were concerned, but the kids come in, they put their masks on, they’re fine. They do a really nice job.”

Children are required to wear masks in schools per an order from Democratic Gov. Tom Wolf. That rule has gotten pushback from parents in some school districts and sparked a stalled effort among state Republicans to overturn the governor’s rule.

At Hershey Middle School, masks are just part of the plan to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Winslow led the way into the cafeteria, where instead of tables, children ate lunch at desks spaced six feet apart. Extra desks lined hallways in case they were needed. A teacher used a microphone and a PA system to let students know when to take up their trays. Students used mobile devices provided by the school to chat with others from around the lunchroom.

Like many protective measures throughout the pandemic, the changes are a compromise, Winslow said. However, they’re worth making if they keep children from getting sick and keep students in school.

That’s already happened once this school year, Winslow pointed out. The elementary school had an increase in cases, and the school switched to online learning for a week.

Unlike last school year, this year the Pennsylvania Department of Health is not requiring schools to close due to COVID-19 cases among students, Winslow noted. Instead, the department offered schools recommendations for when to do so. The Derry Township School District is following those guidelines.

To Winslow, there’s a clear choice: Limit the spread of the virus, or risk going back to online and hybrid learning.

“Overall our community is very supportive of in-person instruction,” Winslow said. “They wanted kids back in school, and despite the way they might feel about masking or some of the different political situations, their goal is for their kids to get a good education and to have them here so that we can provide that for them.”

Brett Sholtis / Transforming Health

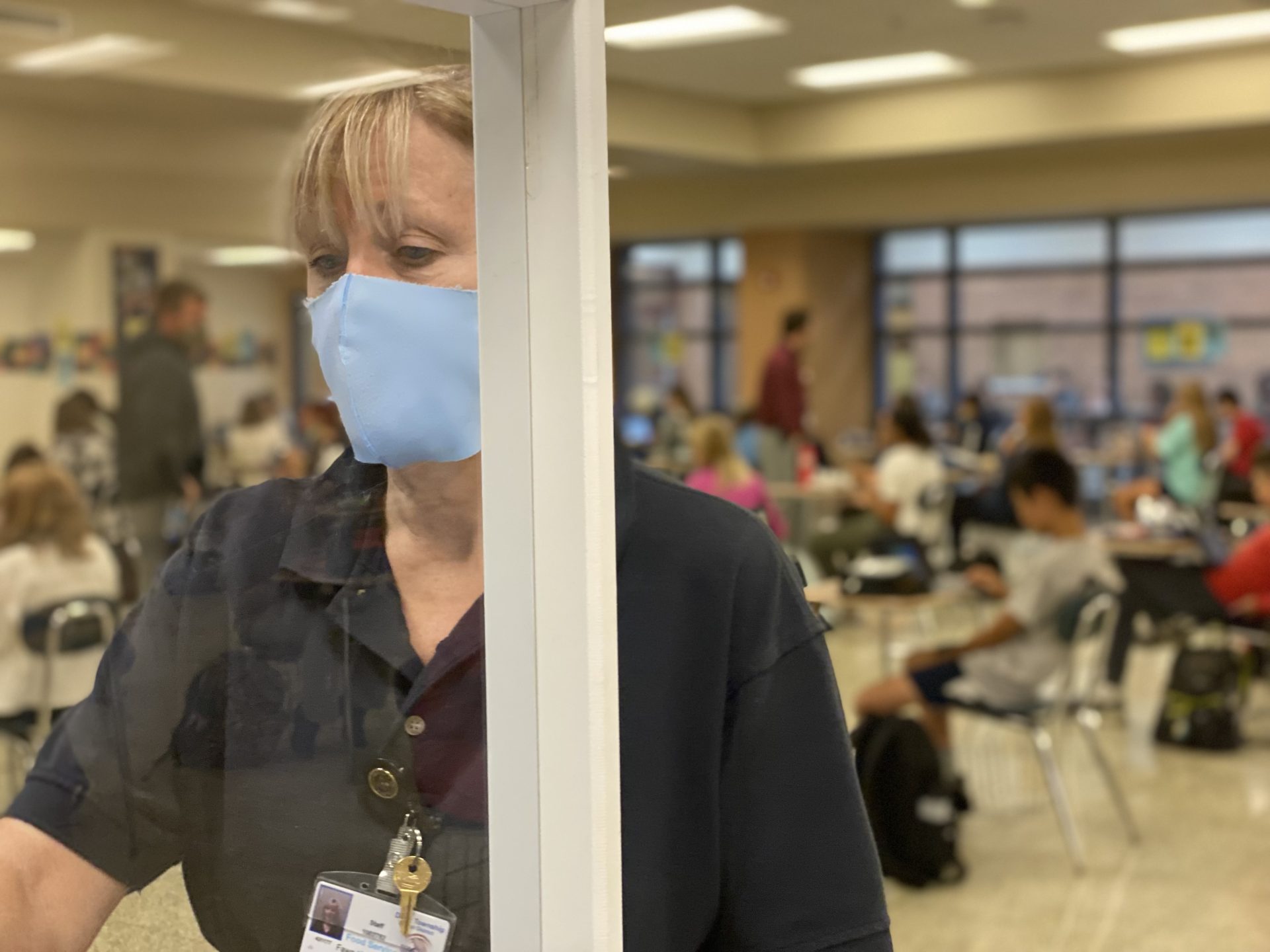

School cafeteria worker Fawn Kunkle-Tucci checks out a student who is getting lunch while in the background eighth grade students sit at desks to eat.

At stake are both the learning potential and well-being of children, Pedersen said. The previous year left kids without many of the support systems they get in school. It was harder for them to talk with a counselor or psychologist. Casual interactions with teachers at the beginning or end of class didn’t translate well to video chat. The school saw an increase in student absences from classes.

“It’s been a chronic, stressful, sustained situation for everybody,” Pedersen said. “And as humans we don’t particularly tolerate prolonged stress well, nor do we particularly tolerate prolonged ambiguity well, and it has been all of those.”

Parents’ concerns about mask wearing come at a time when school boards across Pennsylvania — and around the U.S. — have become political battle grounds.

Conservative groups have poured money into mobilizing parents against public health measures such as masking, and social media posts that falsely tell parents that masks will harm their kids continue to proliferate on platforms such as Facebook.

Some state politicians have stoked those flames, calling masking child abuse. In videos that racked up hundreds of thousands of views on platforms such as Facebook, conservative commentators and activists such as Charlie Kirk have said without evidence that face coverings can lead to mental health issues or suicide.

No matter what is contributing to a parent’s fear, it’s important to take their concerns seriously, said Dr. Titina Brown, president of the Association of School Psychologists.

However, she emphasized that there’s simply no evidence that masks are harmful to kids in any way. There is research suggesting masks have a beneficial effect on student well-being during a pandemic, Brown said, pointing to a study recently published in the Journal of American Medical Association.

“And the researchers hypothesize that positive association is because the students feel safer — they feel like they are doing something that is positive for their physical health — and so it improves that mental health component,” Brown said.

There are of course a few exceptions to this, Brown said. Some special needs students come to mind. But overall, the greater risk is COVID-19.

And keeping children at home also poses challenges, she said. Among other things, it puts more of the burden of education on the parents, who may not have the time or resources to help their kids with technology or their school work.

While masks are harmless for children, the same can’t always be said for prolonged remote learning, according to Stephen Sharp, President of the Pennsylvania School Counselors Association.

Sharp said remote learning posed a complicated series of challenges for parents. While some children had robust support at home, others lived in houses where they didn’t have reliable internet, or where nobody was home to help them.

“There are schools that might have been rich with technology and resources that transitioned to online learning rather easily,” Sharp said. “In some of our most rural and some of our most urban districts, it wasn’t a question of technology, it was a question of whether our students would have food to eat.”

One silver lining, Sharp said, is that the pandemic has drawn attention to the need for more mental health resources at schools. He pointed to a need for lower minimum staffing ratios for school counselors and psychologists. That’s something his group and others have pushed for through legislation. The most recent version of that proposal presently is sitting in the House Education Committee — the place where a similar bill died last session.

Like Sharp, Jason Pedersen at Hershey Middle School said the pandemic has been a learning experience for educators. Teachers at the middle school recently trained on how to recognize mental health needs for students and help respond to students’ needs.

For the near future, wearing masks, changing up the lunch routine, and other small adjustments are the price they all pay to help one another, Pedersen said.

“This is our opportunity to do this for each other, and I think most families would say, I would rather my child being in school, wearing masks — which, granted, are not ideal — but as you heard as we walked down the hall, there’s not a lack of socialization going on.”

The days of journalism’s one-way street of simply producing stories for the public have long been over. Now, it’s time to find better ways to interact with you and ensure we meet your high standards of what a credible media organization should be.