Pennsylvania Attorney General Josh Shapiro

Matt Rourke / AP Photo

Pennsylvania Attorney General Josh Shapiro

Matt Rourke / AP Photo

Matt Rourke / AP Photo

Pennsylvania Attorney General Josh Shapiro

(Hellam Township) — A Wednesday meeting between the Pennsylvania attorney general and a behavioral health care company shed some light on how $1 billion from opioid makers and distributors could be used to help people living with substance abuse disorders—and the brewing controversy over whether cities and counties should accept the money.

Democratic Attorney General Josh Shapiro’s meeting with Pyramid Healthcare executives and behavioral health care advocates comes two weeks after four companies that make or distribute opioids agreed to a $26 billion nationwide settlement. States have 30 days to opt in to the settlement agreement.

It also comes amid growing discussion over whether municipalities should take the funds, and agree to drop their lawsuits, or fight the drug companies in court. Pennsylvania’s largest cities, Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, recently sued the AG over his decision to agree to the settlement.

Pyramid Healthcare CEO Jonathan Wolf told Shapiro that low staffing and high turnover limit the company’s ability to accept people for substance abuse treatment.

The company needs to pay behavioral healthcare workers more, Wolf said. Higher wages, along with incentives such as college assistance and sign-on bonuses — paid for with settlement money — would help to hire and retain more workers.

Those staffing issues come during a time of growing need for services, said Jason Snyder, drug and alcohol director at Rehabilitation and Community Providers Association, also called RCPA. Snyder noted that 5,172 people in Pennsylvania died from overdose deaths in 2020, a 16% increase from the previous year.

Additionally, Pyramid CEO Wolf said money could also go toward “holistic case management” programs that provide things such as housing and employment assistance for people in recovery.

Under the settlement with drug companies Johnson & Johnson, AmerisourceBergen, Cardinal Health and McKesson, Pennsylvania would see about $232 million in 2022, Shapiro said. The state would get $1 billion total over 18 years.

Shapiro emphasized that the money would not end up in the state’s general fund, like what happened with a 2001 settlement with tobacco companies that was criticized for not reaching people affected by tobacco use.

“It can’t go to filling potholes, or pet projects of some politician,” Shapiro said. “It needs to go to treatment.”

Still, many details have not been sketched out. Shapiro said he’s leaving it to others to determine how to best route the funds to their final destinations.

The decision to accept the terms of the settlement has garnered criticism — and resulted in two lawsuits, one from Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner, and another from Allegheny County District Attorney Stephen A. Zappala Jr. Both suits assert that Shapiro’s office cannot make them give up their rights to pursue their own claims.

Shapiro said his goal is to get guaranteed funds to communities. He said cities or counties that reject the settlement could get tied up for years in litigation with the possibility of not receiving any compensation. This move would also decrease the total amount Pennsylvania gets, and would bar a county that rejects the settlement from getting needed funds.

“My job was to negotiate the best deal I could negotiate for the good people of Pennsylvania,” Shapiro said. “We’ve done that, and now over these next 150 days, each municipality will have a choice to make in whether they want to join in this settlement.”

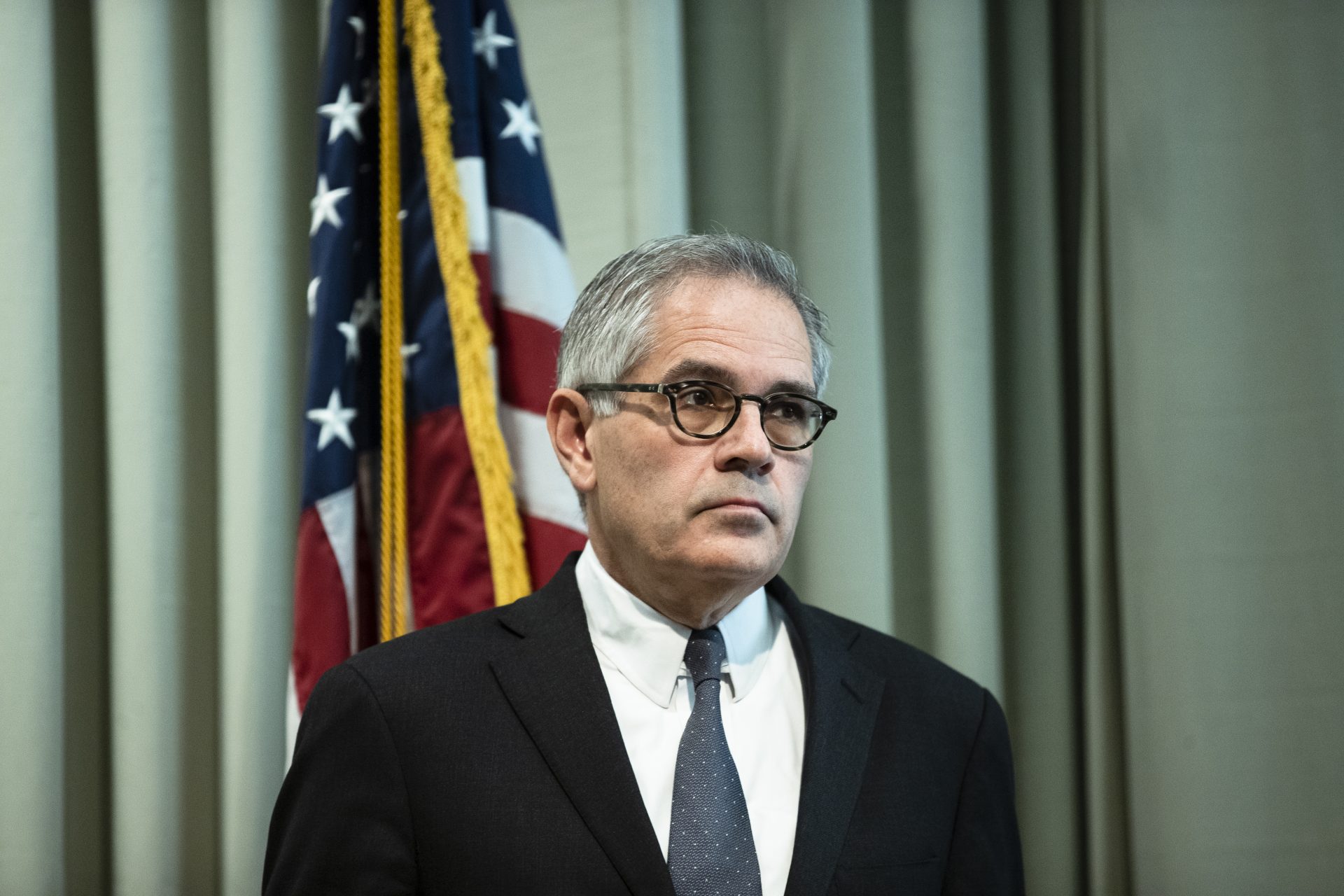

Matt Rourke / AP Photo

FILE PHOTO: Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner speaks during a news conference in Philadelphia, Thursday, Nov. 21, 2019.

Philadelphia DA Krasner disagreed with Shapiro.

“There is nothing about some attorneys general getting in a room with big pharma and talking nice to each other, never filing a lawsuit, never doing full discovery, never using all the legal methods available, never finding out how much harm was done—there’s nothing about their talking nicely, settling for a bag of pennies, from the mayor of Philadelphia saying, ‘You know what, I’m going for more.’”

Krasner said his lawsuit, filed three years ago, is set to go to trial in 2022. The city of Philadelphia also has a separate suit against the companies.

He characterized the terms of the opioid settlement as an effort to “squeeze” cities and district attorneys into dropping their lawsuits. Dozens of counties and cities have sued opioid makers.

Krasner said the funds it would provide don’t match the damage he says was done in Philadelphia.

“I’m not saying a billion is enough, but I am saying, there’s harm done to the city of Philadelphia that’s more than what’s available for the entire state under this settlement.”

A collection of interviews, photos, and music videos, featuring local musicians who have stopped by the WITF performance studio to share a little discussion and sound. Produced by WITF’s Joe Ulrich.

The days of journalism’s one-way street of simply producing stories for the public have long been over. Now, it’s time to find better ways to interact with you and ensure we meet your high standards of what a credible media organization should be.