Convalescent plasma therapy in itself is not new, though its use with patients hospitalized with COVID-19 is still experimental and the Food and Drug Administration only just gave it emergency use authorization Sunday, under pressure from the White House. (With the exception of remdesivir, no drug is proven safe and effective for treating the virus.) People who recover from COVID-19 have antibodies in their blood that have helped them fight the virus. Researchers want to know if the blood of recovered patients can be donated to others with severe cases, to help them fight it as well.

“I would never wish COVID on anyone else. They kept saying, ‘You’re such a young age’ — which I thought was hysterical because I’m in my late 40s — but they were like, ‘You’re strong and vital, and probably take good care of yourself.’ So if I had a horrible reaction and I was in good shape…” Morrison said, trailing off. “To think they could turn my plasma into a cure, and all I have to do is donate blood, why wouldn’t I do that?”

Yet many gay men like Morrison are ineligible to donate blood and convalescent plasma. Men who have sex with men, referred to clinically as MSM, aren’t permitted to donate unless they haven’t had such relations in the past three months. The FDA policy stems from back in the 1980s, when blood-donation prohibitions were put in place during the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

Talk show host Andy Cohen recently spoke publicly about his own experiencewith the donor restrictions. Cohen, who is gay, visited a blood center to donate plasma after recovering from COVID-19, only to be told he wasn’t permitted because of his sexual activity.

Prior to 2015, men who have sex with men couldn’t donate blood at all. Beginning that year, they were allowed to donate only if they hadn’t had sex with a man in one year. In April, the FDA reduced the deferral period to three months because of the need for blood donations during the coronavirus pandemic.

“It’s kind of weird, because you could go in and not say you’re gay. What are they going to do? Investigate you? But people just follow that. It’s like at Christmas, you see the Salvation Army asking you for change, and even though they’re so anti-gay, you still give them money, because it’s helping people,” Morrison said with a laugh.

Before the pandemic, Morrison knew about the FDA restrictions. So he assumed policies around donating plasma were similar. When Jefferson University Hospital informed him and other recovered COVID-19 patients of its coronavirus clinical trials, his assumptions were confirmed. The online questionnaire asked male donors about their sexual history with men.

“To think that there are restrictions because of my lifestyle is ridiculous in 2020,” Morrison said.

“I spend a lot of time working with every city official you can think of, I run a big Mummers group, I’m involved with all parts of the community — gay and straight — I run drag queen storytime, so I constantly work with children, I do children’s education programs. So, not to toot my own horn, but I think I’ve accomplished a lot,” Morrison said. “And they can take that feeling that I’ve worked 24 years helping others, and make that feeling go away just by saying I can’t donate blood — as if it’s dirty or different from other people. It’s the most discriminatory thing I think I’ve ever faced as a gay man.”

In April, New Jersey’s Sheila Oliver, Delaware’s Bethany Hall Long and Pennsylvania’s John Fetterman joined a coalition of lieutenant governors urging the FDA to lift the restrictions. The agency is now participating in a study researching their effectiveness.

LGBTQ+ advocates said while shortening the deferral period to three months was a step in the right direction, the policy is outdated, discriminatory and not science-led.

“This policy, like many criminalization laws that exist in the United States, stem back to a time when HIV and AIDS was coming about, so people who were living in fear passed laws that discriminated against the LGBTQ community,” said Christian Fuscarino, executive director of Garden State Equality. “But we know now, through science, these laws are nothing but discriminatory, not based in fact, and actually hurting people’s lives by not getting as much help as we can, especially during a pandemic.”

The Williams Institute at the UCLA School of Law estimated that 360,000 men who would like to donate plasma are not able to because of these restrictions. Their plasma could help save the lives of more than 1 million Americans.

“Convalescent plasma, I think, is even more valuable than toilet paper right now. And we know this plasma provides antibodies from COVID survivors and helps active infected patients to recover more quickly. So, you have millions of men that could be saving millions of lives,” said Salvatore Seeley, program director of health and wellness programs for the community service organization CAMP Rehoboth.

Fuscarino, of Garden State Equality, has known about the donation policy ever since he was a teenager, when he found out he couldn’t participate in his high school’s blood drive.

“I was certainly hurt, because I live a pretty healthy lifestyle, and for folks in need of blood to not take my blood simply because of who I love was really demeaning and hurtful,” he said.

As an advocate, Fuscarino said, he’s heard from many gay and bisexual men willing to donate blood and plasma — many of whom didn’t know the restrictions still existed until visiting a blood center.

“We hear stories all the time from members of the LGBTQ community, especially gay men, who go in to make a blood or plasma donation only to be told that their blood is not valued or valid to make that donation, and it’s certainly a smack in the face to people who are going out of their way to help others,” he said.

Christian Fuscarino, executive director of Garden State Equality, said restrictions on gay and bi men who want to donate blood and plasma are discriminatory. (Courtesy of Garden State Equality)

A spokesman for the Blood Bank of Delmarva said that of its 79,000 prospective donors in 2019, 14 people were deferred because of the issue.

Seeley said a friend who lives in New York recently faced a similar experience.

“He walked in and saw an ad, like Andy Cohen and other people did, that said, ‘Hey, if you were recently infected or impacted, you could be helpful.’ So, he walked into the center, filled out the questionnaire, but when it came to the screening by a person, because he wrote his orientation, because he was truthful and honest about it, that’s when they told him, ‘Hey, because of your sexual orientation, you’re not allowed to donate,’” Seeley said.

“I think it was a shock to know these homophobic principles still exist. He had to walk away knowing he couldn’t help people in the New York area who needed plasma.”

Dr. Perry N. Halkitis, dean of the Rutgers School of Public Health, is known for his research on the health of LGBTQ populations with an emphasis on HIV/AIDS, substance use, and mental health. He said policies like the FDA’s blood donor restrictions can have devastating impacts.

“The health of gay men is not just shaped by biological or behavioral factors, but also social and structural factors,” said Halkitis, who is also a gay man with COVID-19 antibodies.

“There are numerous theories out there … that indicate that populations that are more at risk for discrimination and marginalization, and these kind of oppressive policies, often have worse health outcomes. So, it takes a toll on the mental and physical health — or as I like to call it, ‘health’ — of gay men,” he said.

How donation-deferral rules originated

In an email, a Food and Drug Administration spokeswoman said, “The FDA is responsible for protecting the public health by ensuring the safety of the blood supply, which depends on the implementation of donor screening measures that are based on available scientific evidence.”

The FDA policy was initiated after the emergence of AIDS in the early 1980s. When the epidemic first became known, health officials documented transmission between men who have sex with men. Before it was called AIDS, it was called gay-related immunodeficiency, because it was thought only men who had sex with men could get it. But AIDS also was soon discovered to be transmitted by blood transfusions and the infusion of clotting factor concentrates in hemophiliacs. Health officials also discovered transmission was possible through heterosexual intercourse and intravenous drug use.

In 1983, the FDA initiated the first blood donor deferral policy based on the limited knowledge it had about AIDS at the time. In 1984, human immunodeficiency virus was established as the cause of AIDS. But before the virus was identified, and prior to the approval of tests for HIV in 1985, thousands of blood-donation recipients became infected. So in 1985, the FDA restricted men who have sex with men and people engaging in sex work and intravenous drug use from donating blood indefinitely.

Even though much progress has been made on HIV prevention and treatment, Halkitis said the stigma surrounding the virus still exists.

“We react to HIV from a place that’s driven by fear and irrational thoughts, and not necessarily science. And I do think the other thing at play here is an ongoing stigma and discrimation against HIV-positive people — but also against sexual and gender minority men and women in this country,” he said.

Dr. Perry N. Halkitis, dean of the Rutgers School of Public Health, is known for his research on the health of LGBTQ populations with an emphasis on HIV/AIDS, substance use, and mental health. (Courtesy of Rutgers School of Public Health)

“It’s a perpetuation of that stigma that manifests in many marginalized populations in our society — whether you’re Black, or Black and gay, or trans and Asian — any marginalized group continues to experience this stigma. And very often, laws and policies are put in place that continue to perpetuate that stigma,” Halkitis said. “State-sanctioned discrimination is one of the biggest problems we have in equalizing the playing field for individuals from marginalized groups like LGBT people, and specifically in this instance gay men.”

Morrison said current blood donor policies reflect the stigma he faced in the 1990s.

“In the ’90s, when I would come out, you know, you do your coming out and all that, and people are like, ‘Oh, you’re gay, you better watch out for AIDS.’ I’m like, ‘You better watch out for AIDS, Mary. What are you talking about? We all have to watch out for AIDS,’” he said.

“It all comes back to this stigma of AIDS being a ‘gay virus.’ They want to get these [coronavirus] antibodies, so why wouldn’t you come to gay people? We take the best care of ourselves, more than anyone else on the planet,” Morrison said.

At the end of 2018, an estimated 1.2 million people in the United States had HIV, including an estimated 161,800 people as yet undiagnosed, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Of the new diagnoses that year, 69% were among men who have sex witth men. However, HIV diagnoses among gay and bisexual men decreased overall by 7% between 2014 and 2018.

HIV diagnoses among straight people also decreased by 10%, the CDC says. However, rates of transmission among those who use intravenous drugs increased by 9%. After men who have sex with men, straight Black women were the group most diagnosed with HIV in 2018.

“[Straight] Black women, who are one of the groups overwhelmingly burdened by HIV, can donate blood without being questioned because they are heterosexual. Yet heterosexual transmission is never indicated as a vector and potential problem for blood donations the way MSM behavior is,” Halkitis said.

He added that the policy also reflects a false stereotype that gay men are overly promiscuous.

“And the truth is, yes, gay men constitute the largest proportion of infections in the United States, but they’re not the only group. So if you’re going to do this with one group, you should do this with all the groups, or none of the groups,” Halkitis said.

Seeley, of CAMP Rehoboth, oversees the organization’s HIV prevention programs. When he became involved in HIV testing 20 years ago, the tests required blood draws, and people waited two weeks for their results. Today, there are finger-stick and mouth-swab options that show results in 10 minutes. HIV can even be detected if someone is infected within a 14-day period.

“So much has changed in how we test for HIV that the policy and evidence should have caught up. That’s why I think this decision is based on homophobia and bad science,” he said.

In 2015, the FDA updated its guidance for blood and plasma donations, setting the one-year deferral standard. But in April of this year, the COVID-19 pandemic pushed the FDA to ease its restrictions again, to ensure that blood supplies wouldn’t be in jeopardy. As stay-at-home orders were announced across the country, thousands of blood drives were cancelled overnight, halting donations.

LGBTQ+ advocates say the loosening of donation restrictions doesn’t go far enough.

“Our nation is in a crisis right now and people need help, and this is why the FDA’s policy change is a sign of progress. But the current crisis demands that we must follow the science and have a complete and immediate end to this archaic and demeaning ban,” Fuscarino said.

Also reduced from one year to three months now because of the coronavirus pandemic are the FDA’s donation deferral periods for people who have gotten tattoos or piercings and those who have traveled to malaria-affected areas.

The blood supply is adequate today. Yet blood centers are concerned about the fall, when many school and college blood drives will be cancelled as classes remain online.

Blood Bank of Delmarva is calling on the community to donate, reporting that blood drives at high schools, colleges, businesses and other organizations used to make up about 40% of its service region’s incoming blood supply. The number of blood drives has dropped by two-thirds because of the pandemic, the blood bank reports.

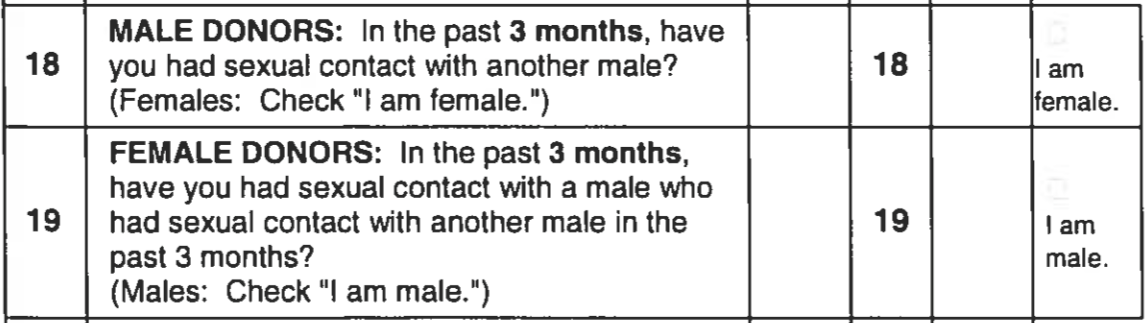

Blood Bank of Delmarva asks 42 questions to screen potential donors, including ask men who have sex with men about their sex life. (Screenshot of questionaire)

The need for plasma varies across geographical regions. The University of Pennsylvania received about 220 donors for its convalescent plasma trials, which have since ended.

America’s Blood Centers, a Washington, D.C.-based advocacy organization, said its members are able to distribute plasma wherever it is needed in the country.

“The challenge is that because antibodies continue to decrease over time we have to constantly refresh our pool of convalescent plasma donors,” said the organization’s CEO, Kate Fry. “We continue to need more and more people to donate for both [blood and plasma].”

The future of donations from gay and bisexual men

To donate blood or plasma, a person must fill out a questionnaire to determine eligibility.

Men are asked if they’ve had sex with other men in the past three months. If so, they’re ineligible to donate — even though donations are tested for a whole host of infectious diseases, including HIV.

“It diminishes our lives, it diminishes our sex lives, it diminishes who we are. It is absurd and hurtful,” Halkitis said. “It is reminiscent to me of when gay men were first getting married, it was, ‘Oh, are you going to have safe sex all the time?’ Do we say that to straight people?”

“There’s a different set of rules for gay people and straight people, for Black people and white people,” he said. “It’s a perpetuation of ‘othering’ that constantly goes on. The bottom line is blood is tested, so what is the problem taking blood from a gay man?”

Blood banks also ask people if they’ve paid for or been paid for sex in the past three months, and if they’ve used needles to inject drugs or steroids not prescribed by a doctor in the past three months. But in general, straight donors are not asked for details about their sex lives. A straight person who engages in unprotected casual sex could be permitted to donate over a gay or bisexual man in a monogomous relationship.

And even if a gay or bi man has been celibate for three months, he can still be prevented from donating if he is taking PrEP, a medication that prevents HIV-negative people from becoming HIV-positive.

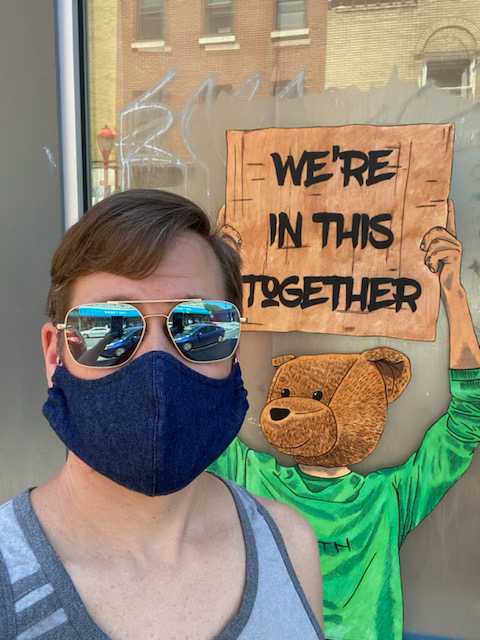

Matt Harker of Philadelphia received a positive COVID-19 antibody test result at the end of July, and he was interested in donating plasma.

“If I can help someone, why not? I would hope someone would help me if I had a bad case,” said Harker, 42.

Being single, he thought he might be eligible to donate since the deferral period had been shortened. But Harker didn’t know that taking PrEP would also preclude him from doing so. He likened the restrictions to “second-class citizen status.”

“It just seems so archaic,” Harker said. “If they’re willing to shorten it from a year down to three months because of an urgent circumstance, it just makes the whole thing feel very arbitrary and convenient. Why do it at all?”

Matt Harker of Philadelphia was interested in donating his COVID-19 antibodies. But he was told he could not donate because he takes PrEP. (Courtesy of Matt Harker)

A spokesman from Blood Bank of Delmarva said decisions to defer donations from people taking medications are based on a medical director’s recommendations. They take into account information from drug manufacturers suggesting that blood collected from someone taking a medication might cause an adverse reaction in a blood recipient.

The FDA is now participating in a study to investigate whether donor deferrals can be based on individual risk assessments. The pilot will enroll about 2,000 men who have sex with men and are willing to donate blood.

This study, which is being conducted at community health centers, could help the FDA determine whether a donor questionnaire based on a risk assessment would be as effective as time-based deferrals in reducing the risk of HIV. The study’s completion date is still to be determined.

A FDA spokeswoman said in an email that the agency is “committed to gathering the scientific data that can support alternative donor deferral policies that maintain a high level of blood safety.”

Blood Centers of America believes eligibility should be based on behaviors, not on sexuality, CEO Kate Fry said.

“All blood centers’ priority is to treat all potential donors with fairness, quality and respect. Our hope, as an industry, is that we can establish donor screening based on individual behaviors in the future — not based on sexual or gender identity,” she said. “We are in favor of the changes FDA has made so far, and hope they will go even further in the future once the data is there.”

CAMP Rehoboth’s Seeley agreed deferrals should be based on behavior rather than identities.

“As a straight cis[gender] person, you are more likely able to donate based on what your risk level is now over someone who says, ‘I am gay,’” he said. “That’s why you have to move to, ‘If I’m a straight person, I got tattoos from a friend that got a kit off a website, I shouldn’t be giving blood,’ or ‘If I have hired sex workers, I shouldn’t be giving blood.’ But if I’m in a monogamous relationship, I should be able to give blood because my risk is low.”

Halkitis said community activism can have some impact, “but ultimately it’s going to reside in the hands of legislators working with public health experts.”

“Very much like the decision making about opening schools around COVID or about wearing masks — science leads the way. And that’s no different from this situation here where science should lead the way. That indicates to us, ‘Hey, it’s not just gay men infected,’ ‘Hey, we’re testing the blood anyway,’ so therefore, why do we need to continue to discriminate when the overwhelming majority of gay men are not HIV-positive?”

WHYY is the leading public media station serving the Philadelphia region, including Delaware, South Jersey and Pennsylvania. This story originally appeared on WHYY.org.