(Beaver Falls, PA)

84-year-old Irene Vigosky spends her Sunday afternoons each fall, like most western Pennsylvanians, watching her beloved Pittsburgh Steelers take the field.

But, this Sunday October 5th, will be different.

It’ll mark the 70th anniversary of when her family learned one of her older brothers died fighting in World War II.

“My mother, one or two nights before the telegram came, dreamt exactly the way it came to be. The doorbell rang and when she went, she had her glasses on and of course as soon as she saw the soldier, she knew what this is going to be (and) let him in,” the western Pennsylvania woman says. “As he was telling her or gave her the telegram, that she took her glasses off and just threw them on the floor, which they did not break.”

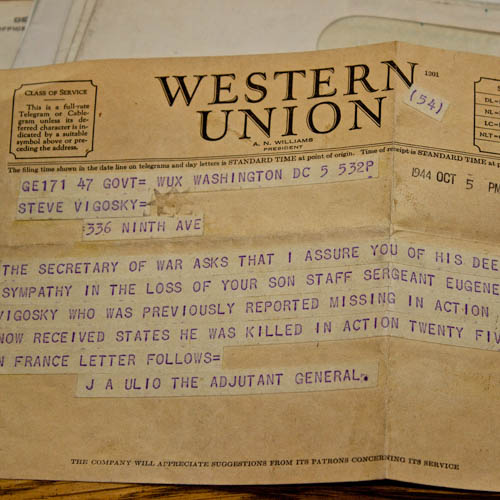

The telegram presented to Vigosky’s mother reads:

“The Secretary of War asks that I assure you of his deep sympathy in the loss of your son, Staff Sergeant Eugene Vigosky, who was previously reported missing in action. Report now received states he was killed in action 25, July in France. Letter follows.”

The notification ended nearly two months of waiting for the Vigoskys, since their second-oldest son had been listed as missing near Saint Lo in France during the Battle of Normandy.

At the time, Irene was 14-years-old.

In her small, second-floor apartment in Beaver Falls, Vigosky, known as “Skee” to her friends, is sitting with her nephew Dave Nemeth as he takes Eugene’s Purple Heart out of its case.

“By the way, this is the first one I ever saw,” he says.

“Let me see..I haven’t seen it in a long time,” she says. “It’s heavy!”

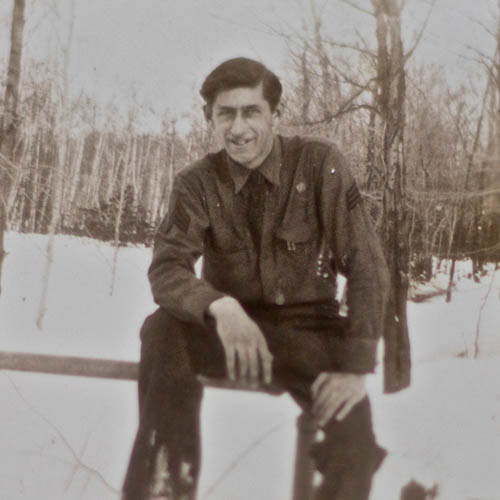

Eugene’s nickname was Pony, but Irene can’t remember why. In fact, it’s hard for her to remember much about her big brother because she didn’t know him all that well.

Pony left home in 1934 when she was only four. He was drafted into the Army and inducted in New Cumberland, Cumberland County, on October 27, 1941, about six weeks before the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Vigosky was listed as having a grammar school education, meaning he likely finished the eighth grade.

He eventually rose to the rank of Staff Sergeant with the 119th Regiment of the 30th Infantry Division.

While not a lot is known about Eugene’s military service, Skee remembers him working as a mortar instructor at Fort Benning, Georgia. In letters home, he would reassure his mother he would not go overseas into combat.

“That I do remember. He wrote, ‘Don’t worry about me. I’m going to be fine, because now I’m this mortar instructor. So, they (the soldiers) come in and out and I’m just going to be here,’” she says. “So, we’re thinking, ‘Boy, before long, he’ll be coming home and be okay.’ But, then came D-Day.”

D-Day, June 6, 1944. The day the largest seaborne invasion in history was launched along five beaches on the coast of Normandy.

Five days later, Eugene and the 30th Division likely hit Omaha Beach to join the vicious day-to-day combat raging inland through the hedgerows and farm fields. It was the kind of fighting where the enemy was sometimes only a few feet away.

Soon after, Nemeth says the tone of his letters changed dramatically.

“The last letter that they got, he says in there, ‘Pray for me because I don’t see how anyone can live through this,’” he says.

To this day, it’s not known how Eugene died — only the date and the place.

No one in the family has been able to make the more than 3,700 mile journey from Beaver Falls to Normandy to visit his grave.

Eugene Vigosky’s will signed on September 21, 1943

Skee’s parents were first-generation Americans.

They met in Pittsburgh after arriving from Hungary.

While she knows how much her father loved his new homeland, she still wonders why he allowed Eugene to be buried in France.

“That I do remember shocked me, because I thought for sure…you know… it’s my brother. They’ll going to bring him home. We’ll put him here, where we can go put flowers,” she says. “His question was, ‘Will it be in France, but in an American cemetery that will be cared for?’ As soon as they guaranteed him that, he said, ‘Then that’s where I want him to be.’”

“But then he might have had the feeling that he was proud his son was there, fighting for this country,” she adds. “So, he would leave him there. I don’t know,” she says quietly. “We might have to take a break here…because, it’s starting to hit me now.”

Tears are starting to roll down Irene’s face. She gets up and leaves the room for a few minutes.

“The Spirit of American Youth Rising from the Waves” is a 22-foot bronze statue is at the center of the entrance to the Normandy American Cemetery.

Keep in mind,

60 percent of the families who lost loved ones during the Battle of Normandy chose to have their sons or husbands returned to the U.S. So, that means over a dozen weeks of fierce, relentless fighting, more than 30,000 American died during the initial push to liberate Europe from Nazi rule.

Her dad’s decision — like thousands of other families at the time — meant his boy would eventually be interred at what is perhaps the most famous overseas U.S. military burial ground. He would forever be looked after by strangers.

The 172-acre Normandy American Cemetery overlooks the bloodiest of the five D-Day landing beaches, Omaha, where Vigosky may have first stepped foot in France.

It’s like a one-two punch of emotions while walking to the entrance.

First are the hushed tones while walking toward the gate, the gentle waves from the water below, and the winds blowing through the pine trees lining the walkways.

Once inside, it becomes visual.

Row after row after row of white Latin Crosses and Stars of David are aligned perfectly in any direction as far as the eye can see. The green grass is immaculate.

It is the final resting place of 9,383 soldiers, sailors and airmen and four women. Another 1,557 are listed on the cemetery’s Walls of the Missing.

As people exit the visitor center to walk among the graves, a recording plays in a constant loop, somberly paying homage to the dead and missing.

“George W. Rarey. Francis T. Walsh. Harlin V. Yates. George H. Hazlett Junior. Andrew Ryan. John D. Shanks. Fred R. Licence. James C. Crouch….”

The cemetery is one of 24 American military burial grounds on foreign soil overseen by the American Battle Monuments Commission. Anthony Lewis has been an interpretive guide at the Normandy American Cemetery for six years.

“I’m a seasonal guide, so I work six months every year to augment the permanent guides that are in the cemetery throughout the whole of the year,” the affable Welshman says.

When the next-of-kin visits, staff members like Lewis escort them to the gravesite of their loved one for a special ceremony. These kinds of gatherings occur three or four times a week and family members are usually transported by a golf cart. Lewis has agreed to drive to Vigosky’s grave site.

One of the pathways leading to the entrance of the Normandy American Cemetery.

“Okay. Here we go,” he says, starting its engine.

On the short trip, the facts and figures can be overwhelming. But, they are are necessary to even come close to understanding the scope of what lies ahead.

The cemetery is divided into 10 plots and every single grave faces westward toward America, the homeland of those who made the ultimate sacrifice.

A father and son lie side-by-side as do 33 of the 45 pairs of brothers buried here. There are three Congressional Medal of Honor recipients and 307 unidentified graves marked “Known but to God.”

“This is Plot E and we need Row Five. So, here we are. Eugene Vigosky, staff sergeant with the 119th Infantry, part of the 30th Infantry Division. Entered service from Pennsylvania. Died 25th of July, 1944,” Lewis says. “There are two options here with all the dates. They either actually physically did die on that particular day or indeed that’s the day the body was recovered.”

In one hand, Lewis is holding a small bucket of moistened sand with a wet sponge and in the other are two flags. He then takes the sand, gathered from Omaha Beach, and rubs it into Vigosky’s engraved name.

“I’ll dust off any excess and then obviously, we’ll have an absolutely perfect engraving with no excess sand in it,” he says. “The sand will eventually bring his name out.”

Lewis notes the sand will dissipate over time with the natural Normandy weather (some sun and a lot of rain).

“It would probably take two or three days to actually wash out,” he says.

The process brings Pony’s name out from the white Lasa marble Latin Cross to the point it can be read from 15 to 20 feet away.

Lewis puts down the bucket and then carefully unfurls the flags — one American and one French — that stand about knee-high. He’s now in a crouch just to the side of Vigosky’s grave stone.

“The American flag we put in the soldier’s right hand and the French flag we put in his left. Obviously, the Americans landed on Omaha Beach as such and it’s just tradition that we put the flag nearest the beach and obviously, the body is here, the head is here and the feet are there,” he says “This is right hand and here is his left. The French flag is always put toward inland territory.”

From Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania, to arguably one of the most hallowed of grounds in U.S. history, Vigosky is one of 1,213 Pennsylvanian’s buried or listed on the walls of the missing here.

Eugene Vigosky’s grave site, after Lewis completed the sanding and placed the two flags into the ground.

Let the number 1,213 sink in, for a moment.

It means Pennsylvania lost more young men than any other state represented in this cemetery.

Each row of graves is numbered three through 43. Anthony Lewis is now walking down Row Five of Plot E. Vigosky’s grave sits at the end of the line of crosses and Stars of David. He’s reading off the names of those from Pennsylvania.

“Pennsylvania. One. Okay. This is Franck Maudie.”

“Two. Wilbert A. Weaver. Again, the state of Pennsylvania. Five.”

There’s no order of burial — not by rank, religion, division, state or date of death.

He’s up to six now.

“James M. Nolan. A private.”

Like in war, fate, destiny or chance chose where a soldier lays and who is alongside of him.

“Here we are. We’re back at Eugene Vigosky’s graveside. He would make it..uh…he’d be number nine,” Lewis says. “Out of 40, yes.”

It’s a somber illustration of how much the liberation of France was paid for in blood, in part by young men from the commonwealth’s steel mills, coal mines and farm fields.

Lewis sees escorting family members and veterans, many now in their 90s, as a huge honor and priviledge. He always makes a point to read them a portion of the speech given by the French president at the cemetery’s inauguration on July 18, 1956.

“These young men who sleep their last sleep here, have earned in history their places in the first-rank of conquerors. When the survivors returned home, the dead remained together in brotherhood as they were in battle,” Lews recites. “Let us ponder the great lessons which we learn from their tombs. We do not forget, we shall never forget, the infinite debt of gratitude that we owe to those who have given all for our freedom.”

Irene “Skee” Vigosky holds photos of her brother, Eugene, from his time in the Civil Conservation Corps in the 1930s.

Back in her Beaver Falls apartment,

Irene Vigosky and her nephew David Nemeth sit and look over pictures of Eugene’s gravesite.

“There he is…that’s Pony,” Nemeth says.

“It’s a good place to pray. A lot of souls there,” Irene adds.

The quiet beauty captured in the photos brings her back to her question of why her father allowed Pony’s final resting place to be so far from home among his brothers in arms.

“I still feel that it had something to do with his love of this country. It’s almost like, ‘Okay, I’ll let you have my son, where he died.’ I don’t know, but that’s what I think,” Irene says as her voice quivers and lowers to a whisper. Tears well under her eyes. “That’s why it’s good to see how they take care of him. That’s why I don’t like being in this again, because it’s like living it all over. Oh dear.”

So much is unknown about what happened to Staff Sergeant Euguene Vigosky and how he came to be in Saint Lo on July 25, 1944 — as the Allies broke out of Normandy and started the fight toward liberating Paris.

More than 3,700 miles separate Pony’s birthplace and final resting place. But, his memory and sacrifice have never been forgotten — not by his last living sibling and not by complete strangers lovingly tending to the marble Latin Cross bearing his name and facing home.

Tom Lambert, the author’s father, pays tribute to Eugene Vigosky.