Bethany Slavic Church in Ephrata.

Bethany Slavic Church in Ephrata.

Bethany Slavic Church in Ephrata.

(Ephrata)- Ilya Tlumach was 7 when he arrived in Lancaster County in 1989 from western Ukraine. His family was fleeing religious persecution under the former Soviet Union.

Ilya’s father, Ivan Justinovich Tlumach, became a founding pastor of Bethany Slavic Church in Ephrata – a Pentecostal church that emerged as a space for refugees of the former Soviet Union who wanted to practice their faith freely.

Many members come from Russia, Belarus, Ukraine and Moldova. Despite the difference in nationalities, the congregation finds unity in their religious faith and their Slavic identity. Members of the church also share the pain of watching Russian troops murder civilians and destroy homes.

“To see brother fighting brother, it’s very tragic,” said Nikita Korablin, who grew up as part of the church. “I look at it, I just, I don’t know, I feel a little bit helpless, very upset.”

Millions of Ukrainians have fled their homes and country. Now, Tlumach and Korablin are among those helping Bethany Slavic Church as it works to raise money to buy and distribute food in Ukraine and help evacuate people out of war zones.

Volunteers for the church’s Ukraine fund are building a database of hosting families and apartments, meeting with local refugee placement organizations. The church will be sponsoring four displaced families that will be arriving in Lancaster County soon to start new lives — just as many of their own families did decades ago.

When Ilya Tlumach tells his story of how he came to Lancaster County as a refugee, he begins with his father, who was born in 1926 in Western Ukraine. As a young man in the 1940s, Ilya’s father, Ivan, worked at a mill providing food for the Ukrainian resistance.

Ilya Tlumach

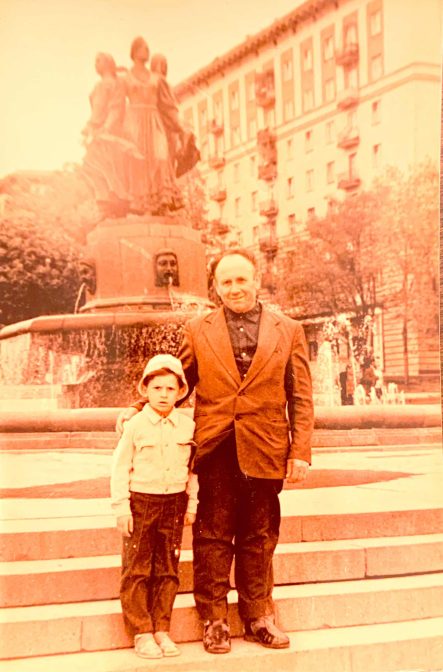

Ilya Tlumach and his father, Ivan Tlumach in Volgograd, USSR in 1988.

“His siblings died, most of them other than one sister died during the famine in 1933,” Tlumach said.

By famine, Ilya is referring to the Holodomor – Ukraine’s famine under Joseph Stalin that killed millions of people.

For helping the Ukrainian resistance, Ilya’s father was given a decade-long sentence of forced labor. After he got out, he joined a church. Practicing Christianity was not allowed in the USSR, so Ilya’s father was sent to prison for five more years for being part of a congregation and working with youth through his church.

By the time he got out, Ilya’s father was in his late 30s. He got married and had 11 children. But from the beginning, the Tlumach family knew they wanted to leave the Soviet Union. The family could not practice their protestant religion freely, so they became part of an underground church. But their faith came at personal price.

Ilya’s siblings were persecuted for not pledging allegiance to Lenin. He heard stories of Protestant children being shamed at school, not being able to participate in sports or go to college.

“Children of practicing Protestants, they were just outcast, shunned by society,” Tlumach said.

His parents worked for more than a decade with humanitarian groups to find a way to leave.

“My mom is a hero in that she fought for that by providing documentation that people were being oppressed, that there wasn’t freedom of speech, that there was persecution,” Tlumach said.

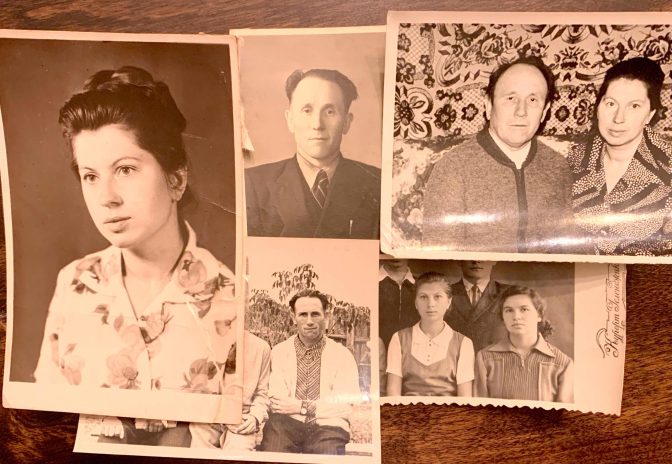

A collection of Tlumach family photos. Ilya Tlumach’s mother, Valentina, is pictured on the left.

Eventually, Ilya’s family fled the country as refugees. They renounced their Soviet citizenship and became stateless.

“We didn’t know anybody at all,” Tlumach said. “Didn’t know the language, didn’t know anyone. My parents sold everything that they had, and I came here.”

The family settled into their new home with the help of two Mennonite churches that served as sponsors.

In the early 1990s, Nikita Korablin was a toddler when he arrived in Lancaster County.

Korablin is from the Far East region of Russia – a town called Nakhodka. His grandmother is Ukrainian. His family also became part of Bethany Slavic Church’s growing community of Soviet refugees.

“They chose this area because there’s a large Mennonite population who made it their mission to help emigrate Russian Ukrainian immigrants to this area, so it kind of just naturally happened that way,” Korablin said.

Korablin, now 30, is a youth pastor at the church.

Like the Tlumach family, Nikita’s family was looking for a place where they could practice their faith freely. He was too young to know what it was like under the Soviet regime, but he heard stories from relatives.

“They were made to feel ashamed of their beliefs. They were barred from going to certain colleges and universities and stuff like that. Their future was limited, I guess you could say,” Korablin said.

Some members of the church, including Tlumach and Korablin, are not just recalling their own oppression while feeling the pain of fellow countrymen enduring war. They have family on both sides of the conflict.

Andrey Teleguz, a member and administrator for the church’s Ukraine War Fund, has family in southwestern Ukraine and his wife has family in Russia.

Lyudmila Teleguz, also a member of the church and Andrey’s sister, is originally from a town in Ukraine called Chernivtsi. She says family members who are volunteering for the church’s efforts in Ukraine send her pictures and videos.

“We just sit with my husband watch and cry all the time,” she said

Korablin still has cousins living in the country. He has family connections in Ukraine through his wife’s family.

Tlumach, now 40, was born in Lutsk, a city in western Ukraine that was recently bombed by Russian forces.

“I see myself personally getting involved in refugee resettlement, refugee support,” Tlumach said. “I’ve been very fortunate and blessed with a lot of connections, business, and otherwise, just socially, and I just see people hungry and willing to help.”

Gabriela Martínez is part of the “Report for America” program — a national service effort that places journalists in newsrooms across the country to report on under-covered topics and communities.

Get insights into WITF’s newsroom and an invitation to join in the pursuit of trustworthy journalism.

The days of journalism’s one-way street of simply producing stories for the public have long been over. Now, it’s time to find better ways to interact with you and ensure we meet your high standards of what a credible media organization should be.