Utibe R. Essien, M.D., M.P.H., is a health services researcher at VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System Center for Health Equity Research and Promotion and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh.

Courtesy of Utibe Essien

Utibe R. Essien, M.D., M.P.H., is a health services researcher at VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System Center for Health Equity Research and Promotion and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh.

Courtesy of Utibe Essien

Courtesy of Utibe Essien

Utibe R. Essien, M.D., M.P.H., is a health services researcher at VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System Center for Health Equity Research and Promotion and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh.

Courtesy of Utibe Essien

Utibe R. Essien, M.D., M.P.H., is a health services researcher at VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System Center for Health Equity Research and Promotion and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh.

In 2018, Dr. Utibe Essien, an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh, was studying a cohort of 12,000 patients in a large atrial fibrillation registry. Atrial fibrillation, which disproportionately affects Black patients, is a common cardiac rhythm disturbance that can cause substantial disease and death. Though Black patients are typically less likely to be diagnosed with this condition, Essien says, they are more likely to develop strokes and more likely to die of atrial fibrillation once diagnosed.

Doctors and clinicians depend on oral anticoagulants to treat the condition, which can reduce stroke risk by up to 70% and is considered the standard of care in patients with moderate to severe stroke risk.

But in that 2018 study, “we found … that Black patients were less likely to receive these blood thinners and especially the newer class of blood thinner medications or direct oral anticoagulants,” Essien said.

The general understanding within the medical literature was that those racial disparities were due to social and economic factors such as access to insurance, income, and education level. Essien, who wanted to better understand the mechanisms for the treatment disparities, turned to data from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Every patient in the VA has access to a uniform list of medications that can be prescribed.

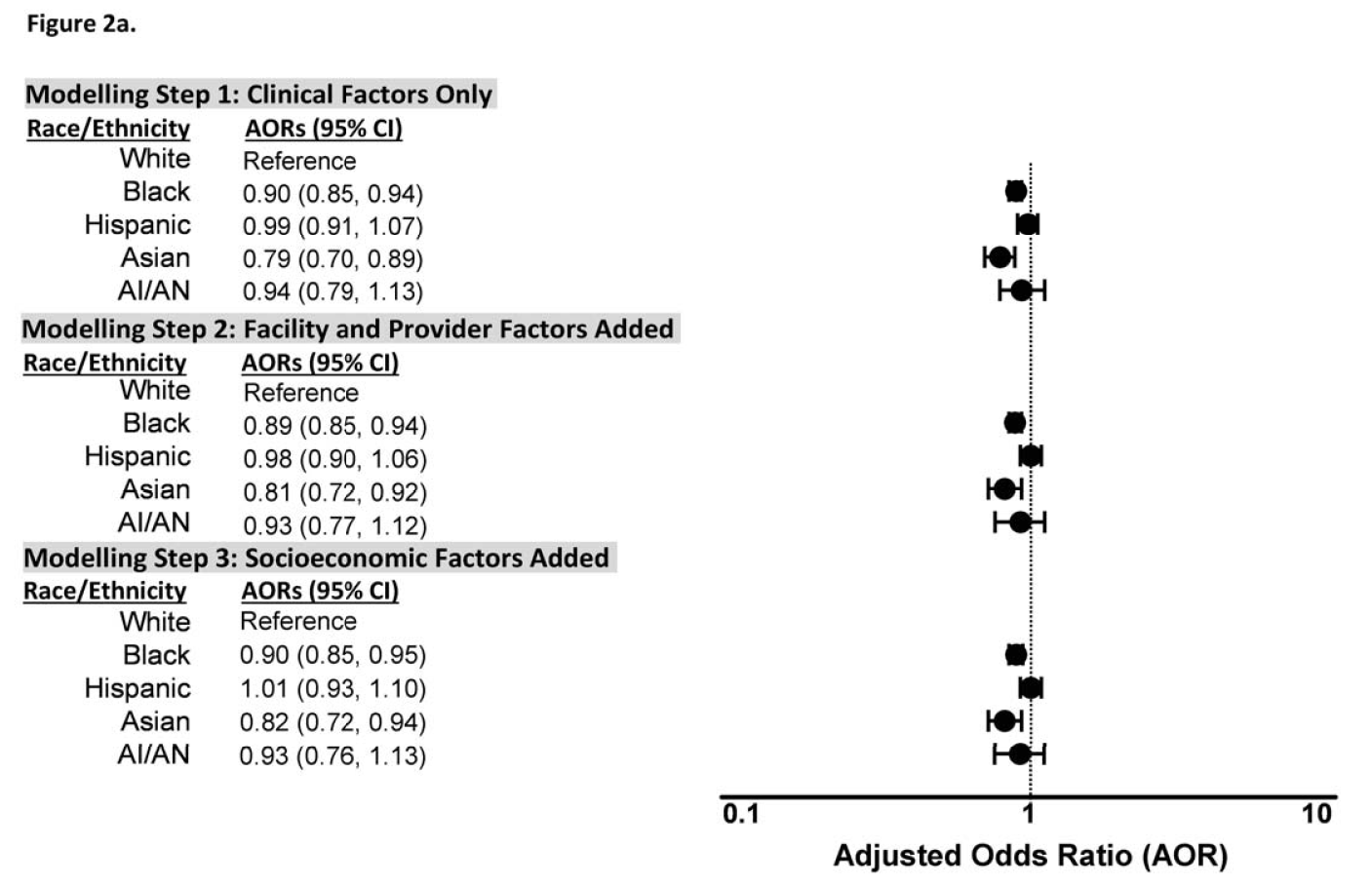

Adjusted odds ratios for initiation of any oral anticoagulant (OAC) therapy by race/ethnicity for patients with incident atrial fibrillation: Black and Asian patients had significantly lower adjusted odds ratios of receiving any OAC therapy than white patients in the fully adjusted model.

“So regardless of where you’re getting your care — here in Pennsylvania or out in California — you have the same access to the medications that every other veteran has, and you’re paying the same amount,” said Essien.

The idea was to look at this specific health system, where access to medication and insurance were the norm, to see whether racial disparities in treatment still persisted. So in 2019, Essien and fellow researchers examined data from more than 111,000 VA patients across the country with atrial fibrillation from 2014 to 2018. After adjusting for clinical, sociodemographic, provider and facility factors, the new study, recently published, revealed that Black and Asian patients were significantly less likely than white patients to be prescribed blood thinners. So even in the VA’s integrated health care system, which traditionally provides more equitable access to prescription medications, the racial disparities persisted.

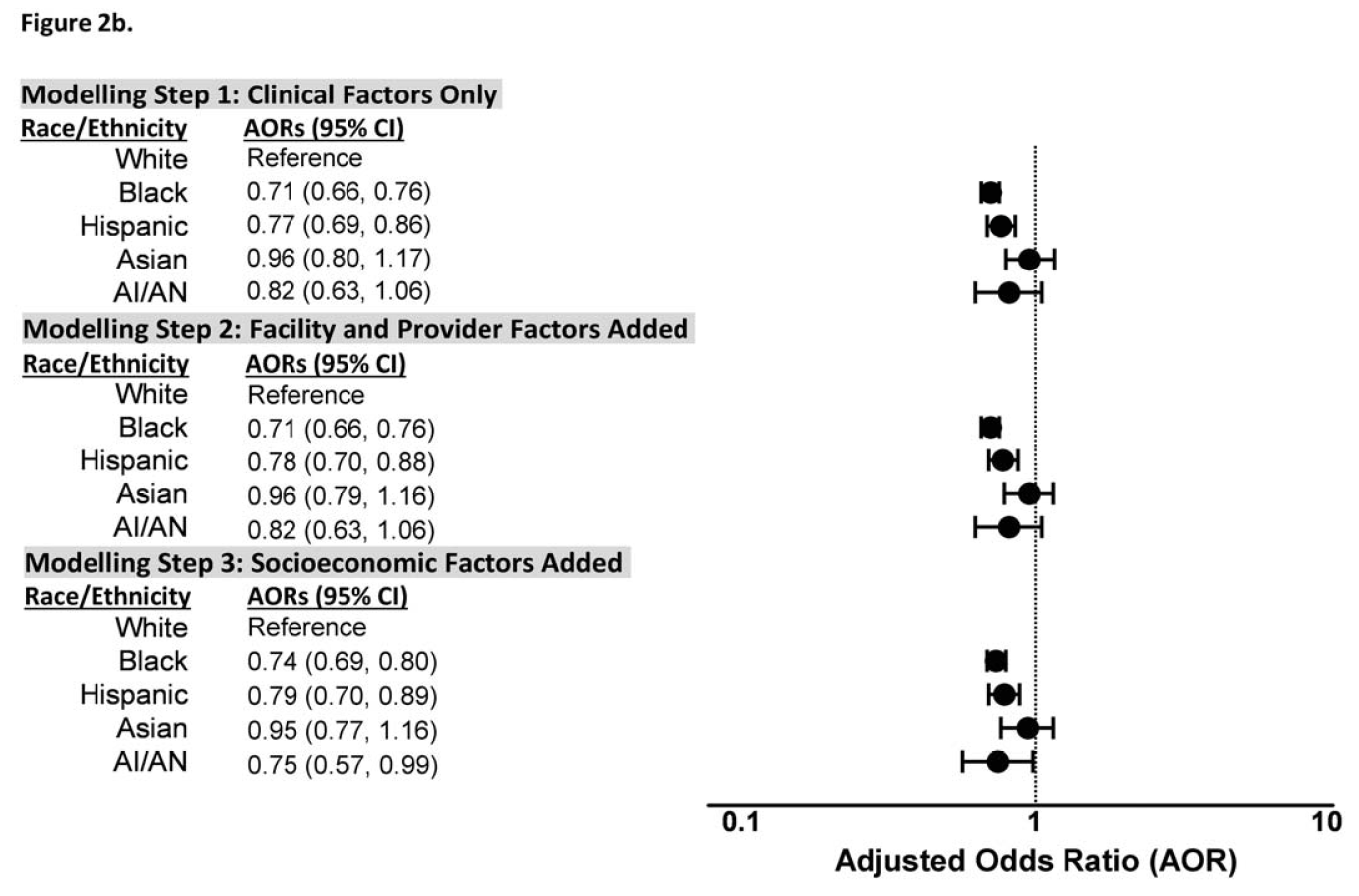

Dr. Jared Magnani is an associate professor of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh and a co-author of the new study. Even when patients of color were prescribed anticoagulants, they were less likely to get the newer, standard-of-care medications to treat their condition.

For years, a drug called warfarin was the only oral anticoagulant available for stroke prevention in patients, but it had some complicating risk factors. According to Magnani, when people are treated with anticoagulants, there is a background risk of stroke and that risk is higher in individuals who are taking warfarin than in those who are taking the more contemporary medications.

“And people who are on warfarin have a greater risk for bleeding events than those on the more contemporary agents,” said Magnani.

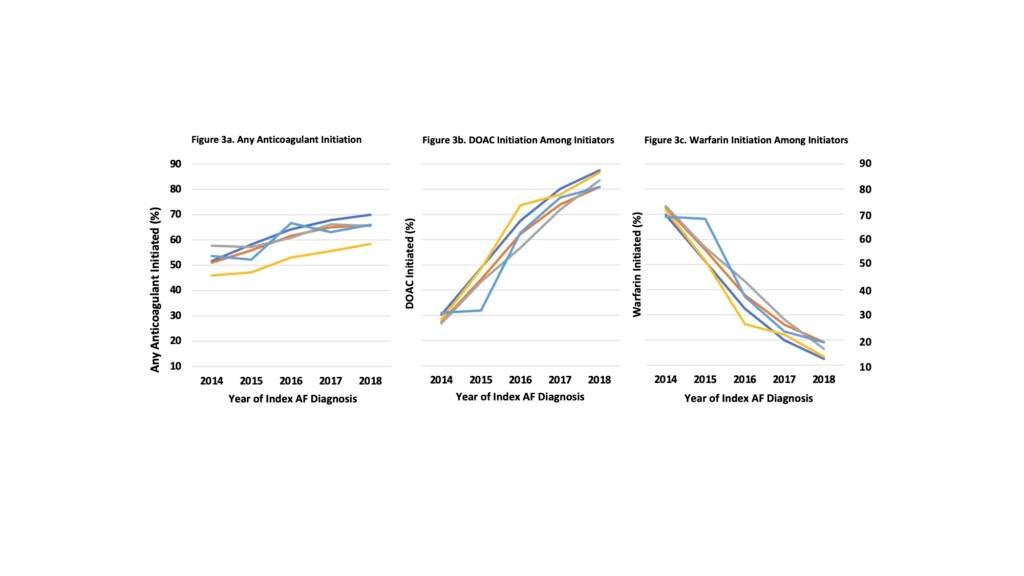

Time trends for initiating any anticoagulant, direct oral anticoagulant, and Warfarin by race/ethnicity for patients with incident atrial fibrillation.

Warfarin also requires patients to monitor their diets and other medications to ensure there are no negative interactions, said Essien. Plus, patients must come in every four to six weeks to get their warfarin levels checked.

“It’s not just an inconvenience to a lot of patients, but it’s quite challenging to control,” said Essien. “And there [has] been almost a decade-plus of data showing that patients who have more challenging social situations really have a difficult time taking warfarin and being well-controlled on it. And if you’re not well-controlled on warfarin, you have a high risk of developing a stroke.”

Over time, newer medications known as direct oral coagulants have proven to show superior outcomes, cost effectiveness, safety, and patient adherence compared to warfarin. But when Essien and fellow researchers looked at the kind of anticoagulants patients of color were prescribed in the VA system, they found that Black, Hispanic, and American Indian/Alaska Native patients were less likely to receive those newer, more effective — and now standard-of-care — blood thinners.

Adjusted odds ratios for initiation of direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) therapy by race/ethnicity for patients with incident atrial fibrillation: Black, Hispanic, and American Indian/Alaska Native patients had significantly lower adjusted odds ratios of receiving DOAC therapy than white patients.

In a system like the VA in which patients have complete access to care, Magnani said, there shouldn’t be a patient-level barrier that impedes individual access to care. But he and fellow researchers still found enormous treatment disparities by race for stroke prevention in a chronic condition.

“I think that we’re seeing the downstream effects of social inequities and structural racism that are broadly a part of our society,” said Magnani. “So we are not able to assess, for instance, individuals’ proximity to care, individuals’ relationships with their physicians and how they engage in receiving care, attitudes, and the treatment differences by race among the providers themselves.”

Magnani stressed that uniform access to medications does not mean uniform access to care. He said there may be individual and system-level barriers that preclude people from having access to care.

“For instance, if people live in neighborhoods where there is less access to transportation or they themselves have barriers because of their work, because of their own financial constraints or other competing social demands, then their access to care may be limited,” said Magnani. “In turn, they may be less likely to be referred for an ambulatory evaluation where atrial fibrillation can be diagnosed and subsequently treated.”

According to Essien, additional study and qualitative interviews with patients and doctors are needed to further understand what may be driving the racial differences in treatment. On the provider level, he said, there may be implicit or unconscious bias at play.

“When we think about [a patient’s] ability to start newer therapies … we wonder, do they have the financial support, do they have the caregiver support, or are they going to be able to tolerate this new treatment?” said Essien. “These are decisions that we quickly make on a dime, and we really do have varying ways that we make those decisions depending on the way a patient looks in front of us.”

And most likely, system-level barriers like a patient’s likelihood of getting referred to a cardiologist or patient access to top medical specialists play a role. Essien said he believes there is an opportunity for future research to include interviews with patients and doctors to learn what happens in the exam room, which treatments doctors are offering patients, and whether patients are accepting those recommended treatment options.

Support for WHYY’s coverage on health equity issues comes from the Commonwealth Fund.

Sometimes, your mornings are just too busy to catch the news beyond a headline or two. Don’t worry. The Morning Agenda has got your back. Each weekday morning, host Tim Lambert will keep you informed, amused, enlightened and up-to-date on what’s happening in central Pennsylvania and the rest of this great commonwealth.

The days of journalism’s one-way street of simply producing stories for the public have long been over. Now, it’s time to find better ways to interact with you and ensure we meet your high standards of what a credible media organization should be.