With new infections rising around the country due to the delta variant, reports of breakthrough cases among the fully vaccinated can be worrisome.

Mario Tama / Getty Images

With new infections rising around the country due to the delta variant, reports of breakthrough cases among the fully vaccinated can be worrisome.

Mario Tama / Getty Images

Mario Tama / Getty Images

With new infections rising around the country due to the delta variant, reports of breakthrough cases among the fully vaccinated can be worrisome.

This story was updated July 29 to reflect new research.

New data on the delta variant is coming in, and it’s not looking good. The currently authorized vaccines are still very protective, especially against hospitalization and death. But when it comes to getting an asymptomatic or mild case of COVID, they may not be quite as protective as they were against earlier strains.

And, here’s the part that really could change your day-to-day life: It seems vaccinated people who get breakthrough infections may be able to transmit the virus, according to the director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Rochelle Walensky.

“On rare occasions, some vaccinated people infected with the delta variant after vaccination may be contagious and spread the virus to others,” she told reporters Tuesday, citing unpublished CDC data from recent outbreak investigations. “This new science is worrisome.”

That led the CDC to advise that even if you’re fully vaccinated, you should wear masks indoors if you live in a place with “substantial” or “high” levels of coronavirus transmission.

Still, people who’ve been vaccinated may rightly be asking: Are breakthrough cases becoming more common because of the delta variant? Could I get sick or get a family member sick?

Here’s what to know about breakthrough cases in the context of delta, and what scientists are doing to track the vaccines’ efficacy:

Bottom line: Don’t panic. So far, research shows the current vaccines are holding up well against the delta variant. For instance, data from the U.K. suggests the Pfizer vaccine is 88% effective at preventing symptomatic COVID-19 from the delta variant after two doses. And an earlier study from the U.K. found that it is 96% effective against hospitalization.

If you do get infected (which is not likely but possible), the vaccine should help you keep from getting seriously sick. “Breakthrough infections, they tend to be mild — they tend to be more like a cold,” said Dr. Carlos del Rio, professor of medicine and infectious disease epidemiology at Emory University.

Severe cases among vaccinated people are possible, but extremely rare — the vaccines dramatically reduce the risk of serious illness that leads to hospitalization or death. And 97% of those currently hospitalized with COVID-19 are unvaccinated, according to Walensky.

For context, as of July 19, out of 159 million fully vaccinated people, the CDC documented 5,914 cases of fully vaccinated people who were hospitalized or died from COVID-19, and 75% of them were over age 65. It’s not clear how many of these breakthrough infections were caused by the delta variant, but that’s now by far the dominant variant in circulation.

The chances of getting seriously ill after being vaccinated are higher for those with certain health conditions that affect the immune system. Dr. Marc Boom, president and CEO of Houston Methodist, said that at his hospital, 90% of the patients with COVID-19 are unvaccinated. The small percentage of vaccinated patients who do end up hospitalized, he said, “have underlying significant health risks — like cancer, like [organ] transplants — that probably prevented them from mounting a full immune response to the vaccine.”

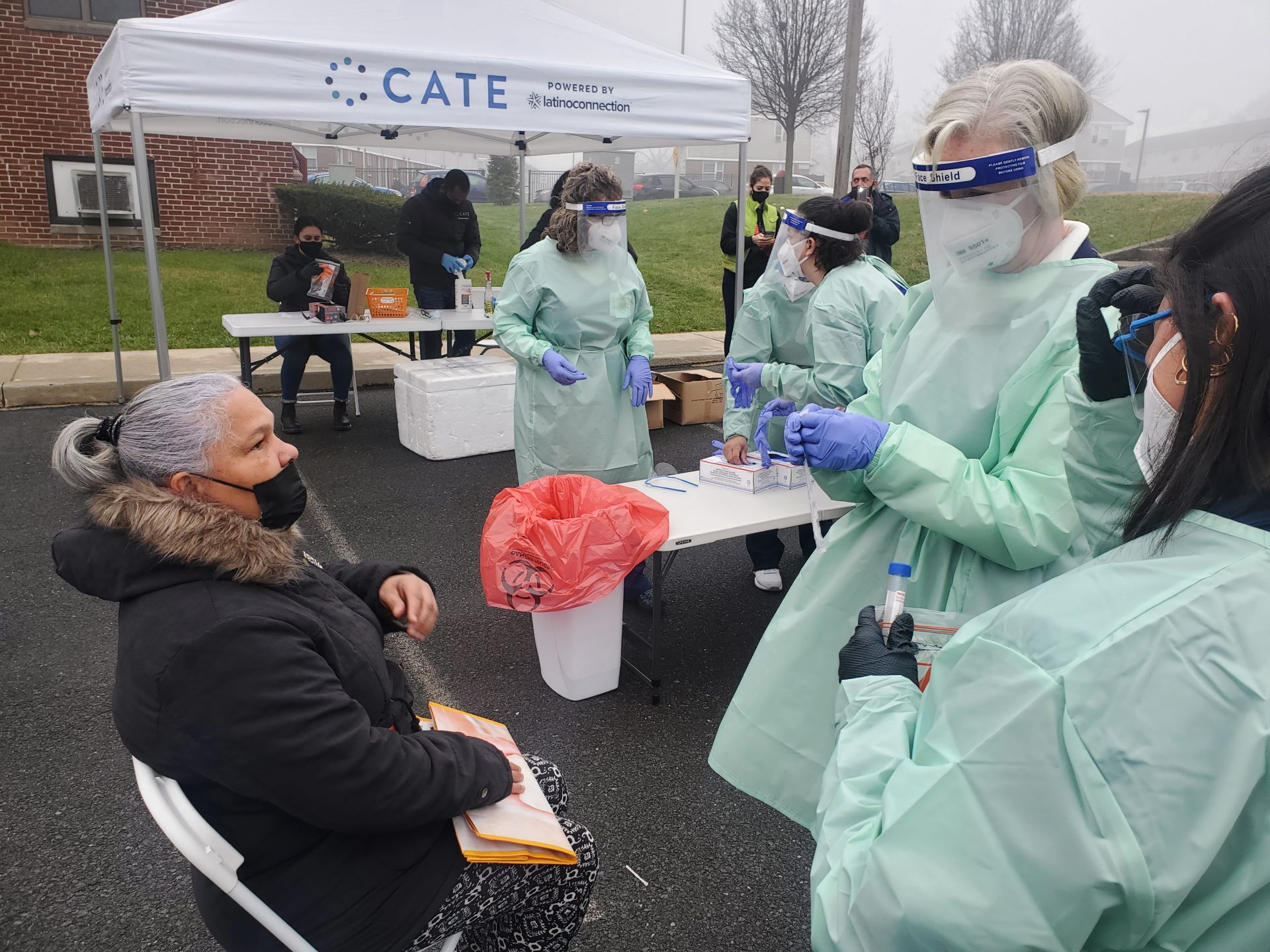

Anthony Orozco / WITF

Luz Maria Colon Muñiz gets tested for COVID-19 Saturday after arriving to Reading from Puerto Rico earlier in the week.

Although health officials initially believed that it was unlikely people who got infected after being fully vaccinated could transmit the virus, new research suggests they can. Part of the reason, experts say, may be that the delta variant has been shown to replicate quickly and copiously in people it infects.

As Walensky explained Tuesday, CDC has conducted outbreak investigations, and analyzed the viral load in the people who got infected, breaking out the vaccinated from the unvaccinated. “When we examine the rarer breakthrough infections and we look at the amount of virus in those people, it is pretty similar to the amount of virus in unvaccinated people,” she said.

CDC is continuing to follow those breakthrough cases to understand whether this higher-than-expected viral load leads them to actually infect other people.

The viral load data was part of the reason CDC changed its masking guidelines for vaccinated people, Walensky said, but the agency has not yet released the data she described.

“CDC has been good about releasing data along with policy,” said Saad Omer, director of the Yale Institute for Global Health. He’s hoping this data will be made public soon as well, so he and other infectious disease experts can look it through.

Until recently there was very little data to help answer the question of whether the vaccinated could get long-haul COVID after a breakthrough case. Some experts thought it was unlikely. But a new study from Israel, suggests there’s a chance vaccinated people may be at risk for long COVID-19 symptoms.

As NPR reported, researchers at the Sheba Medical Center in Israel tracked nearly 1,500 vaccinated health care workers — among them, 39 people got sick with COVID, and of those, seven people had symptoms that lingered beyond six weeks.

Gili Regev-Yochay, who led the study, said these patients had symptoms like severe fatigue, loss of taste and smell, muscle pain and headaches.

“You could say these are mild symptoms, but disturbing enough that some of them didn’t even return to work,” she said.

It could be that this is a false alarm, and that these cases are even more rare than this study suggests, or that these symptoms do end up going away relatively quickly and don’t plague people for months like long COVID. Nevertheless, infectious disease experts described the findings as concerning.

“This study is the first to give us an indicator that we may be seeing long COVID even after vaccination, said Dr. Eric Topol, a professor of molecular medicine at Scripps Research. “We had hoped that when you get vaccinated even if you did have a breakthrough infection, you would have enough of an immune response that would block this protracted symptom complex.”

Scientists stress more research is needed to understand this issue. In the meantime, “the safest thing to do is to avoid being infected altogether,” says virologist Angela Rasmussen of the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization at the University of Saskatchewan in Canada.

That might mean — in addition to vaccination — breaking out masks again, re-upping good hand hygiene and getting more air circulating when gathering indoors.

“The mitigation measures that we have put in place previously will still work against the delta variant — it’s not being transmitted by some other route,” Rasmussen added.

There’s no exact number of breakthrough cases nationally. It would be difficult to count the asymptomatic breakthrough cases, because the U.S. isn’t testing nearly enough to catch them all. And in fact, the CDC stopped keeping a running tally of mild breakthrough cases in May.

But that’s not necessarily a problem, said Emily Martin, epidemiology professor at the University of Michigan. “You don’t want to test everybody — you don’t need every positive to be identified,” she said. “You just need to understand how the positives that you’re finding represent the whole pie that you’re not seeing.”

The CDC runs carefully designed surveillance systems (which try to find pie slices that are representative) and does burden estimation (calculations you use to fill in the rest of the pie). It’s a process that’s already done every year with the flu, Martin said, to assess how well the flu shot is working when the vast majority of people who get the flu are never tested.

Now, the CDC is doing the same thing to monitor COVID-19. Hospitals and health departments are sending the CDC detailed information about certain cases of vaccinated patients who are hospitalized with COVID-19.

“We’d like to have a sample of the virus so that we can understand the viral load, so that we can sequence it, we can understand their symptoms and their risks that potentially put them in that situation,” the CDC’s Walensky told a Senate panel last week.

At the same time, the agency is doing ongoing vaccine effectiveness studies at long-term care facilities, academic medical centers, hospitals, and among health care and essential workers. “We’re doing many of those studies across the nation,” Walensky said, explaining that these allow the CDC to get an accurate picture of the real rate of breakthroughs among vaccinated people and whether that’s changing over time.

“That is a more systematic way of measuring breakthrough cases,” Martin said. Realistically, health officials can’t count every case, so this careful, long-term surveillance, along with calculations to extrapolate those findings, gives a fuller picture of how much virus is really out in the community.

There’s basic arithmetic at play: As more people get vaccinated, even if breakthroughs are rare, a rising number of cases will be among the vaccinated.

“Even with a 95% efficacious vaccine, you will have one in 20 vaccinees who are exposed get the disease,” said Dr. Kathleen Neuzil, director of the Center for Vaccine Development and Global Health at the University of Maryland. The important thing to note is that “the overwhelming number [of cases] are among the unvaccinated,” she said.

Certainly, with the delta variant taking over — which spreads about two to three times faster than the original strain — there will be more cases among everyone, vaccinated and unvaccinated, said John Moore, professor of microbiology and immunology at Weill Cornell Medicine.

“But its ability to infect fully vaccinated people is much less than those who are not vaccinated,” he said. “In other words, the vaccines still work, just a bit less well.”

Saad Omer of Yale put it this way: Previously you might have thought your vaccination as “providing a bit of a force field, but that’s not the case anymore,” he said. “It’s still pretty strong armor. But it’s penetrable armor.”

Epidemiologist Martin said that although it’s concerning to see places — like L.A. county — where a growing portion of positive tests are in vaccinated people, that’s not the metric she’s tracking to see if the delta is evading the vaccines.

Rather, she said, “I’m looking for an indication that a higher percentage of vaccinated people are getting infected than previously.”

She and other public health experts are watching for that carefully.

Allison Aubrey contributed reporting.

Get insights into WITF’s newsroom and an invitation to join in the pursuit of trustworthy journalism.

The days of journalism’s one-way street of simply producing stories for the public have long been over. Now, it’s time to find better ways to interact with you and ensure we meet your high standards of what a credible media organization should be.