Supporters of President Donald Trump protest outside the Pennsylvania Convention Center in Philadelphia, Sunday, Nov. 8, 2020, a day after the 2020 election was called for Democrat Joe Biden.

Rebecca Blackwell / AP Photo

Supporters of President Donald Trump protest outside the Pennsylvania Convention Center in Philadelphia, Sunday, Nov. 8, 2020, a day after the 2020 election was called for Democrat Joe Biden.

Rebecca Blackwell / AP Photo

Rebecca Blackwell / AP Photo

Supporters of President Donald Trump protest outside the Pennsylvania Convention Center in Philadelphia, Sunday, Nov. 8, 2020, a day after the 2020 election was called for Democrat Joe Biden.

(Harrisburg) — Today’s Congressional signoff on electoral college votes is usually a formality. But this year it’s attracting scrutiny because outgoing President Donald Trump has baselessly attacked election integrity, and has tried to overturn the results of the Nov. 3 election.

Some Pennsylvania Republicans have supported Trump’s efforts, including by filing their own lawsuits after Nov. 3 and failing to compromise in negotiations over changing state voting laws during the months leading up to the election.

The controversy surrounding today’s vote continues the electoral upheaval that characterized 2020 because of Trump, the coronavirus pandemic and national unrest sparked by police brutality but rooted in civil rights abuses including voter suppression.

Pennsylvania has faced its own challenges in this environment — many of which were apparent even one year ago.

At that point, Pa. election officials had already been saying for months they were worried about launching new voting systems during a presidential election year in the swing state while implementing new election rules enacted via Act 77 the previous fall.

Here’s what unfolded:

Jan. 7: State Rep. Garth Everett (R-Lycoming) announces that, after seven terms, he won’t seek re-election and will retire after the session ends in 2020.

Marie Cusick / StateImpact Pennsylvania

FILE PHOTO: Rep. Garth Everett (R- Lycoming)

Everett was chairman of the chamber’s State Government committee, where voting and election legislation typically originates.

On the Senate side, the committee’s top post had been temporarily filled for months by state Sen. Kristin Phillips-Hill (R-York) since the resignation of former chair Mike Folmer after his arrest for child pornography possession. Folmer publicly acknowledged his crimes and was sentenced to eight years of probation.

Folmer, who served four terms, had been credited for his role negotiating Act 77 amid acrimony among GOP legislative leaders and the Democratic Wolf administration.

The GOP ultimately names Sen. John DiSanto (R-Dauphin/Lebanon), then just starting his second term, as chair.

Jan. 14: In a special election for Pennsylvania’s 48th Senate district – which Folmer had represented – Dauphin County voters use direct recording electronic machines (DREs) one last time before the touchscreen devices are retired after more than 30 years in service.

Dauphin was the last of the commonwealth’s 67 counties to buy new voting machines in keeping with Gov. Tom Wolf’s mandate and a federal lawsuit settlement rooted in a recount attempt by the campaign of 2016 Green Party presidential candidate Jill Stein.

Stein, meanwhile, was suing again because she contended the state shouldn’t have certified one voting machine being used by Philadelphia and by Northampton and Cumberland counties. Philly voters found the ExpressVote XL’s touchscreens oversensitive during its debut in fall 2019, while the devices outright failed to tabulate results in multiple races in Northampton County. The problematic rollout prompted more court cases, one of which is pending in Commonwealth Court.

Matt Rourke / AP Photo

FILE PHOTO: Steve Marcinkus, an Investigator with the Office of the City Commissioners, demonstrates the ExpressVote XL voting machine at the Reading Terminal Market in Philadelphia, Thursday, June 13, 2019.

Feb. 4: Wolf proposes a state budget that election directors say doesn’t include enough money for counties to adhere to Act 77.

Feb. 18: State election officials acknowledge in court they don’t have a clear contingency plan in the event the lawsuit seeking to decertify certain voting machines succeeds.

Feb. 20: Counties raise the alarm during a legislative hearing that lawmakers need to change the rules to allow them to start pre-processing ballots before polls open for both the primary and general election, given the avalanche of mailed ballots anticipated as the pandemic discourages in-person voting.

Otherwise, they warn, results could take days or weeks to determine.

At the time, Pennsylvania was just one of four states that didn’t allow any ballot processing ahead of Election Day.

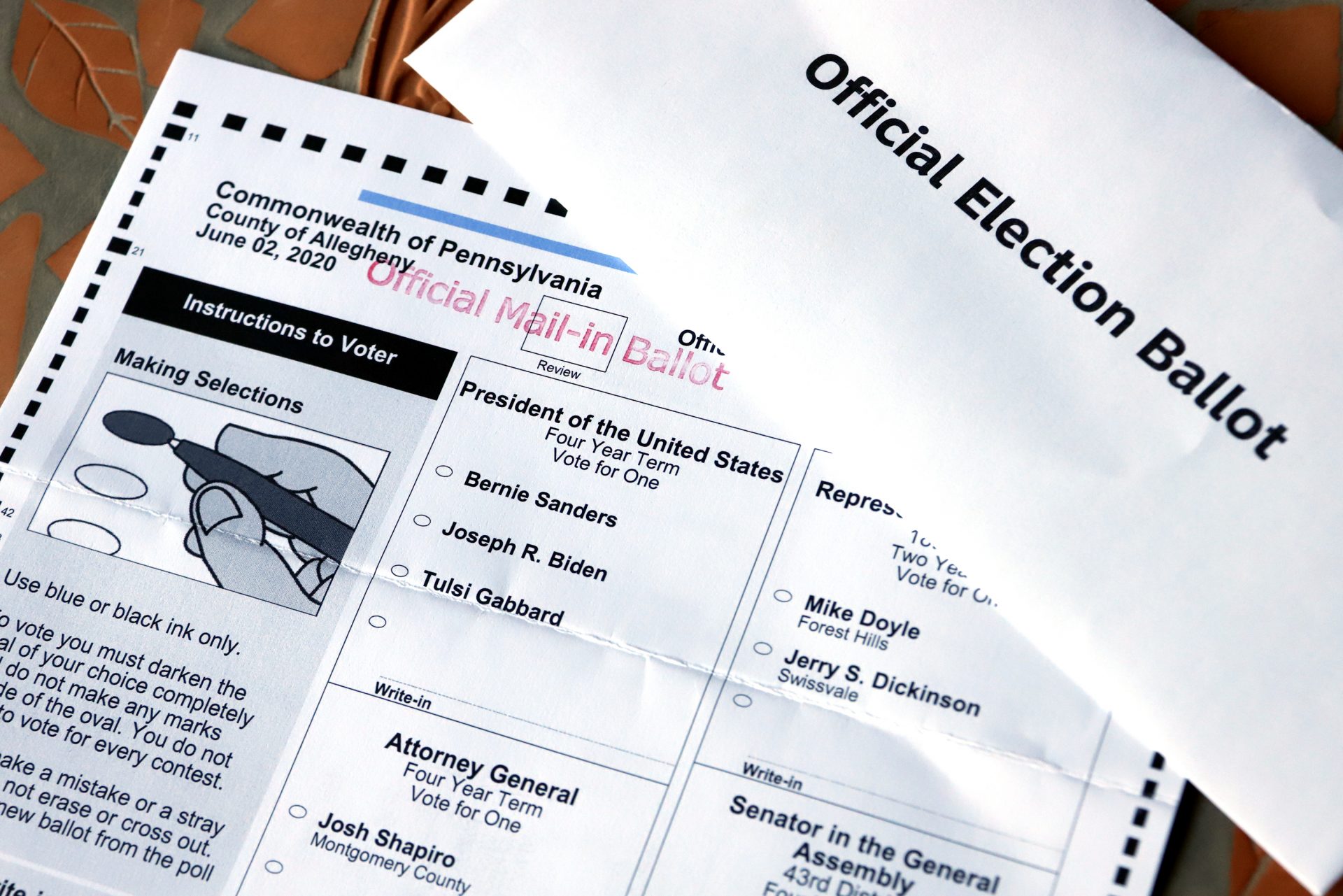

Gene J. Puskar / AP Photo

This May 26, 2020 file photo shows an Official Democratic General Primary mail-in ballot and secrecy envelope, for the Pennsylvania primary in Pittsburgh.

Election workers processing mailed ballots would encounter two envelopes: an outer mailing envelope, which includes a voter affidavit and barcode for tracking, and an inner “secrecy” envelope to shield the ballot from observation through the outer envelope and/or after it’s been removed from that envelope.

Feb. 26: Counties edge closer to getting the promised reimbursement for their new voting machines when the Pennsylvania Economic Development Financing Authority (PEDFA) approves a $90 million bond deal, despite initial misgivings about the structure running afoul of state guidelines.

Counties had started flagging concerns about stocking enough PPE, recruiting and training election workers (predominantly retirement-age adults particularly vulnerable to the virus), and securing venues for polling places as COVID-19 eliminated the option to use some traditional sites such as nursing homes.

March 12: State Rep. Kevin Boyle (D-Philadelphia/Montgomery) introduces a bill that would send mail-in ballots to all voters on the state’s dime.

March 17: Special elections for state legislative districts encompassing four counties run smoothly, despite the pandemic and 11th-hour calls to postpone the contests.

March 27: Wolf signs a bill delaying the April 28 primary to June 2.

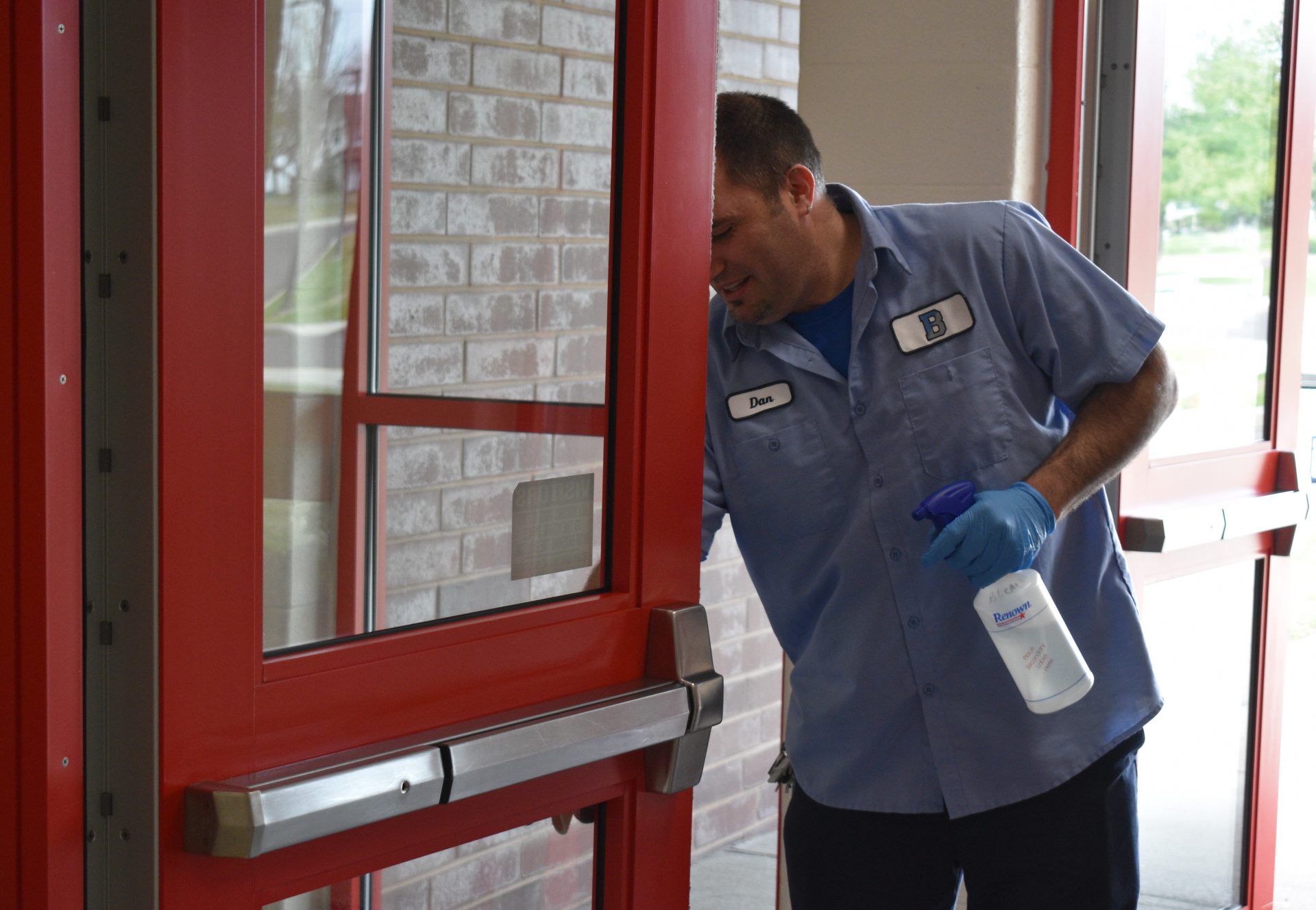

Emily Previti / PA Post

FILE PHOTO: Dan Mortimer, a custodian at Cornwell Elementary School in Bensalem Township, cleans doors leading into the polling place for two precincts during the special House district 18 election.

Counties also find PPE to be at a premium and, with just weeks to go until the primary, struggle to find enough masks, gloves and other supplies to stock polling places – the majority of which are slated to open as usual for in-person voting.

April 27: A coalition of advocacy groups files a lawsuit seeking to give voters more time to return their ballots by mail.

April 30: A federal judge dismisses the Stein lawsuit over the ExpressVote XL (Pennsylvanians would report few, if any, issues with the machine during in-person voting for the primary June 2).

That litigation had become an afterthought as election directors struggled under the crush of mailed ballot applications.

Act 77 gave Pennsylvanians permission to vote by mail without an excuse for the first time, so an increase was expected. But officials had projected the uptick would be about 20 percent or so – not the tenfold growth that ended up happening largely due to public health concerns. COVID-19, meanwhile, left fewer workers to help manage the deluge, with the virus causing callouts and social distancing-driven workspace changes.

County officials appeal to state lawmakers to change the law to allow ballot pre-processing to start before polls open – a refrain that would continue through the general election, to no avail.

May 15: The Pennsylvania State Supreme Court dismisses the lawsuit seeking to extend the commonwealth’s mailed ballot return deadline.

May 26: Just a week ahead of the primary, a federal judge orders the Pa. Department of State to offer voting methods to better accommodate visually impaired voters.

A few months later, DoS would roll out a different system more specifically designed for visually impaired voters before the general election.

May 29: A Commonwealth Court judge denies another attempt to extend Pennsylvania’s ballot return deadline by a week.

Some counties also had been trying for the same, without success, through their local courts of Common Pleas.

Meanwhile, lags in updating DoS polling location information risk confusion for voters — particularly in counties where officials consolidated a high number of voting sites.

Kate Landis / PA Post

FILE PHOTO: Voters walk along the steps of the York County Courthouse on June 1, 2020, to deposit their ballots in a drop box ahead of the Pennsylvania primary.

June 1: About 14 hours before polls open for the primary, Gov. Wolf executive orders six counties to accept ballots that arrive after the statutory deadline of 8 p.m. on Election Day until 5 p.m. the following Friday. A seventh county secured a local judicial order enabling the same.

That three-day grace period would be expanded for the general election to apply statewide — and the state GOP would take its legal challenge of the rules all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, where it’s slated for consideration during the next SCOTUS session beginning Friday. Republicans have acknowledged in court filings that they recognize 2020 results won’t be affected by anything that happens with the case.

June 3: The day after the primary, just three counties are finished counting absentee and mail-in ballots.

Results take longer in many cases due to the increase in mailed ballots.

Even in counties that get through the mail-in processing relatively quickly, provisional ballots cause worse delays. The issue would re-emerge in November when counties reported having more than 125,000 provisionals to process and Trump’s campaign challenges several thousand in majority Democratic counties.

June 9: Lawmakers pass a bill asking the Pa. Department of State to publish a report Aug. 1 detailing the primary.

Despite calls from Democrats and nonpartisan organizations for changes such as an earlier start for pre-processing, most legislators balk at taking action because they say they need data for guidance.

June 22: Nearly three weeks after the primary, all counties have finished processing mailed ballots.

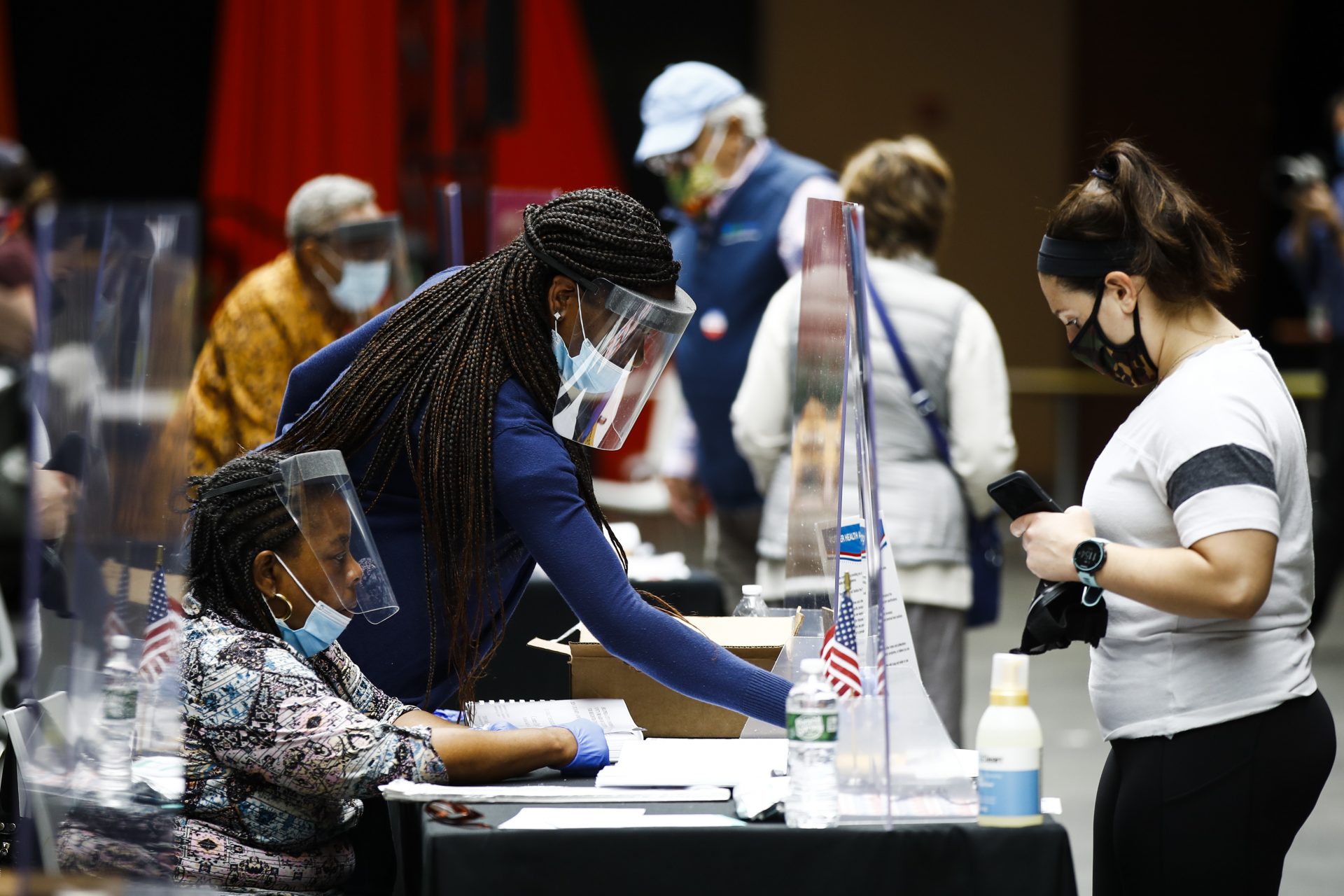

Matt Rourke / AP Photo

Election workers, left, check in voters before they cast their ballots in the Pennsylvania primary in Philadelphia, Tuesday, June 2, 2020.

June 23: The state House of Representatives starts working on an election bill, even though the primary report won’t be ready for more than a month.

Everett and Boyle say they hope to get as much work done as possible ahead of the report’s release to maximize counties’ time to adjust to any resulting changes.

June 26: Trump’s campaign files a federal lawsuit over Pennsylvania’s election rules, seeking to ban mailed ballot drop boxes, allow poll workers to serve in any county (a recipe for voter suppression, advocacy groups warn) and require counties to reject so-called “naked” ballots received without a second internal envelope.

The case marks the start of Trump’s onslaught of election litigation in Pennsylvania in 2020, though his court actions would start in earnest after he lost Nov. 3.

July 12: The Pennsylvania Democratic Party files a lawsuit in state court meant to counter the federal case brought by the Trump campaign.

In addition to changing the mailed ballot return deadline to a week after Election Day, the Dems seek a court order letting counties develop their own ballot collection plans and requiring them to accept those received without a second internal secrecy envelope. Ultimately, this case would be dismissed.

July 23: Political leaders and election officials testify before state lawmakers to what they think needs to change about Pa.’s election laws to expedite ballot counting and improve security and voter access Nov. 3.

July 31: The Pennsylvania Department of State announces pre-paid return postage for all mailed ballots using federal CARES act funding.

For the general election, Pa. voters casting a ballot by mail would get complimentary postage in nearly every county (exceptions included Forest and Perry).

Aug. 1: The Pennsylvania Department of State releases the report on the primary requested by lawmakers.

DoS recommendations included changing Pa. law to:

Aug. 9: More than one week after the report’s release, voting rights advocates and county election directors say Pa.’s at high risk for a chaotic election because legislators haven’t started reform negotiations in earnest.

Matt Slocum / AP Photo

In this Oct. 13, 2020, photo, an envelope of a Pennsylvania official mail-in ballot for the 2020 general election in Marple Township, Pa.

Meanwhile, Trump admits withholding money from the United States Postal Service because he’s likely to lose if enough people vote by mail. The admission comes after public outcry over delivery delays, in general, as well as specific concerns about their implications for the election. Service disruptions are caused by carrier callouts due to the pandemic and USPS equipment removals and overtime cutbacks ushered in by Trump’s new postmaster general.

Sept. 2: Pa. House Republicans move an election bill through the chamber without Democrats’ support, and Gov. Wolf says he’ll veto the measure if it passes the Senate and lands on his desk without changes.

Sept. 17: The state Supreme Court issues three election-related decisions in one day.

Two apply to voting procedure, with one extending Pa.’s mailed ballot return deadline by three days and another upholding the commonwealth’s rule that poll watchers can only work within their county of residence. The third removes Green Party presidential candidate Howie Hawkins from the ballot for not adhering to rules for filing to run for office.

Pennsylvania Republicans later petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court to intervene in the ruling. SCOTUS declined to do so before the election, but is expected to consider the matter more generally during its next session that starts later this week. The GOP has acknowledged 2020 results won’t be affected. Although SCOTUS gave Pa. permission to tally them, the grace period ballots — at least 8,500 statewide, by WITF’s tally of county-reported figures — remain uncounted.

Sept. 30: Pa. House Republicans push for a committee that would investigate elections, over objections by Democrats and nonpartisan organizations that it would interfere with the vote Nov. 3.

The GOP starts to advance the majority-led panel with a resolution – which, unlike a bill, is veto-proof. But the resolution’s second and final vote never happens because a House Republican’s positive COVID-19 test abruptly ended the session, and the initiative never regains momentum.

Oct. 9: A Philadelphia judge dismisses the Trump campaign’s attempt to get access for poll watchers at ballot drop boxes and satellite election offices.

Oct. 10: A federal judge dismisses the Trump campaign’s lawsuit seeking to ban drop boxes and challenging other state voting rules, including those governing poll watchers.

Voting rights advocates remain concerned about poll watching and its potential for voter intimidation, as WITF explored in this story and this one in partnership with Spotlight PA.

At this point, the legislature still hasn’t acted on a couple key election reforms traditionally viewed as nonpartisan, such as letting ballot pre-processing begin before Election Day, as most states do.

Former elected officials had admonished the inaction and lobbied for state lawmakers to make the changes.

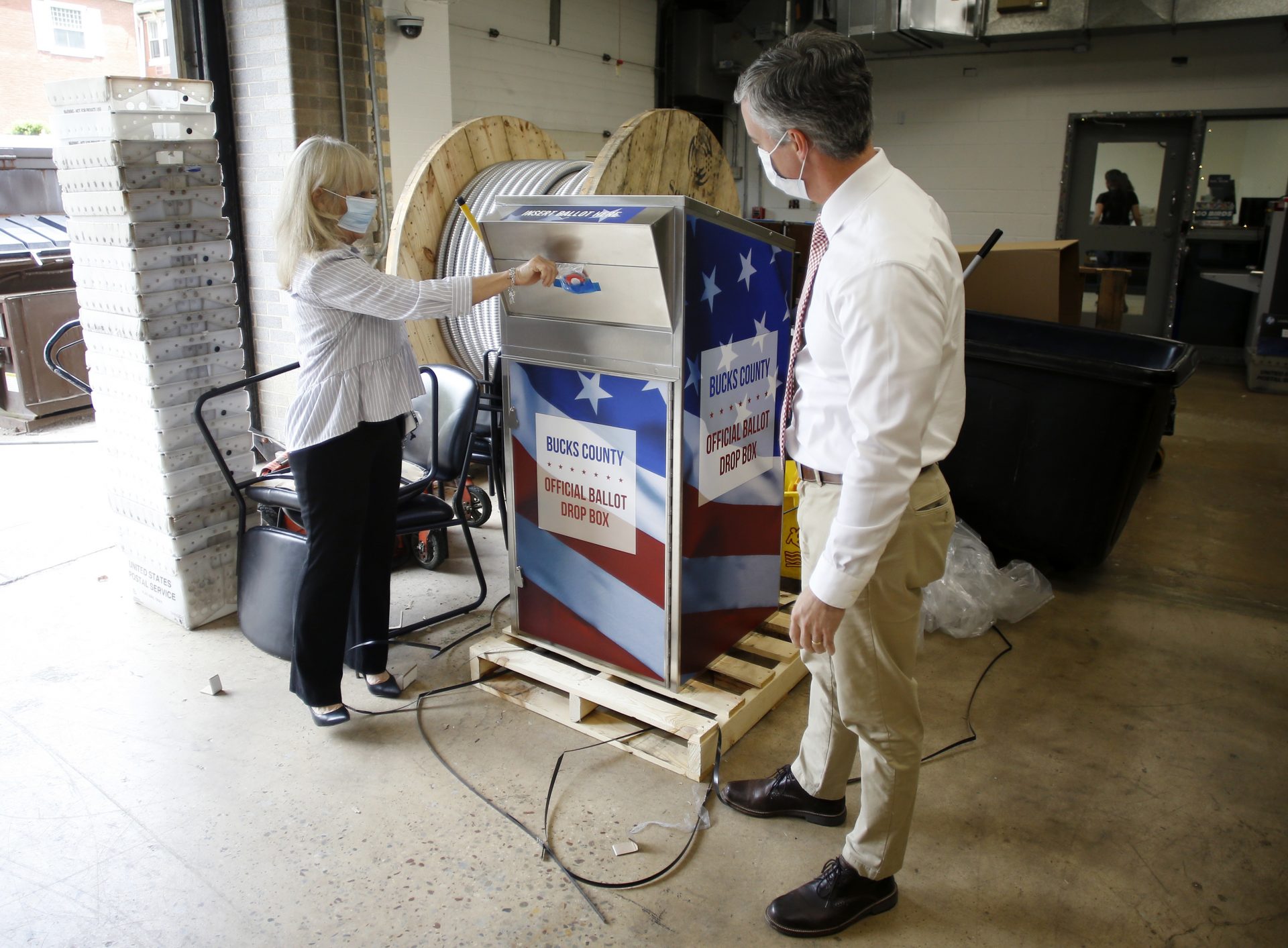

Matt Slocum / AP Photo

FILE PHOTO: In this May 27, 2020, photo, Bucks County commissioners Diane Ellis-Marseglia, left, and Robert Harvie unpack a new ballot drop box at the county’s administration building prior to the primary election in Doylestown, Pa.

Counties had been doing what they could, otherwise, to prepare. They purchased equipment like envelope openers to try to speed up ballot processing. They also offered ballot drop boxes and expanded election officer hours to improve access for voters, who took advantage of the additional options.

Closer to the election, Wolf and Boockvar implore voters to hand-deliver ballots due to persisting mail service disruptions.

Oct. 23: The State Supreme Court rules counties cannot reject ballots solely because the voter’s signature doesn’t match what’s on file in the registration database.

Nov. 3-4: President Trump falsely asserts he’s “winning Pennsylvania” and makes other false claims during a speech delivered within hours of polls closing.

At that time, Pa. counties had tallied more than a million mailed ballots, with another 1.5 million to go. Half a million more were outstanding, and, given the worsening mail slowdown, it was possible any number of them could arrive within the three-day grace period. And 15 percent of voting precincts, home to hundreds of thousands of voters across more than a dozen counties, hadn’t reported any in-person results on election night.

Provisional ballots had yet to be counted. More than 125,000 provisionals were cast statewide, according to what counties tell WITF in the days after the election. Processing them would take days or weeks, depending on the county.

Trump repeats the claim the following day, when far too many votes remain to be counted to call the contest.

Julio Cortez / AP Photo

A worker scans mail-in ballots through a counting machine before they are counted, Wednesday, Nov. 4, 2020, at the convention center in Lancaster, Pa., following Tuesday’s election.

Nov. 7: The Associated Press and other news outlets call Pa. — and the presidency — for Joe Biden, even though Biden leads by fewer votes than there are uncounted ballots.

Later, the AP explained it accounted for provisionals using sampling — and the projected result held.

Nov. 9: The Trump campaign files a federal lawsuit challenging the results, claiming that the president was unfairly disadvantaged because Republican-majority counties rejected ballots with technical errors while Democratic-majority counties attempted to contact voters to address the issues. The claim was not true: some Republican-heavy counties similarly facilitated ballot error corrections.

Experts call the case a “longshot,” but in this WITF story they lay out their concerns for how it might disrupt the vote count.

The campaign, meanwhile, tries to drum up evidence of voter fraud, including with cold calls to registered Republicans in Philadelphia and elsewhere.

It also challenges thousands of provisional ballots in Democratic-dominant counties — a strategy that disproportionately targets voters of color. Ultimately, it fails.

Some attention starts to shift to the electoral college. Typically routine, its affirmation of states’ presidential winners took on new significance because of scrutiny and challenges — however unmoored — over every aspect of the election process. GOP leaders, however, pledge to resist pressure to interfere.

Nov. 10: Philadelphia election officials report receiving threats.

Nov. 17: Trump’s attorney Rudy Giuliani goes to court in Williamsport, Lycoming County, for a hearing in the lawsuit challenging Pennsylvania’s results.

The case alleges a constitutional violation in counties’ different approaches to letting voters fix mailed ballots with technical errors such as a missing signature on the outer envelope. Giuliani was joined by a couple of Pa.-based lawyers (one tried to quit at the last minute with the rest of the legal team, but was kept on the case by the judge). Proceedings were marked by the public access phone line crashing and meandering commentary from Giuliani.

Nov. 19: Boockvar says her home address and phone number were posted on right-wing social media hub Parler along with messages urging users to confront her, and she acknowledges threats have been made against election workers across the state.

Nov. 21: Trump’s federal lawsuit over ballot error correction policies differing among Pa. counties is dismissed.

The campaign’s appeal is rejected five days later: “Free, fair elections are the lifeblood of our democracy. Charges of unfairness are serious. But calling an election unfair does not make it so. Charges require specific allegations and then proof. We have neither here,” 3rd Circuit Judge Stephanos Bibas wrote.

Nov. 23: All but a few counties certify presidential election results in time to make Pennsylvania’s deadline, as the bipartisan state Legislative Budget & Finance Committee rejects a request from Republicans to conduct what a couple Democrats say would be a duplicative audit of the 2020 election.

Nov. 24: Gov. Wolf and Secretary of State Kathy Boockvar certify the commonwealth’s presidential election results despite a couple counties’ final certifications still outstanding.

Nov. 25: A Commonwealth Court judge grants a preliminary injunction sought in an election lawsuit by U.S. Rep. Mike Kelly (R-16), ordering Wolf, Boockvar and other election officials to stop certification efforts.

The state Supreme Court promptly overturns the ruling, allowing certification to proceed and allaying fears that the matter would prevent Pennsylvania from seating its electors and confirming Biden as the winner and recipient of Pa.’s 20 electoral votes.

Kelly — who argued Pa.’s law allowing vote-by-mail without an excuse violates the state constitution — persists, with an appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court. The case is dismissed without further comment from the justices.

Republican state lawmakers sow doubt over election results, including by staging a majority policy committee meeting at a Gettysburg hotel. The event amplifies disinformation from the president and his supporters, including Giuliani and legislators themselves.

Few participants wore masks; within days, a couple lawmakers release public statements confirming positive coronavirus tests.

Julio Cortez / AP Photo

Members of the Pennsylvania State Senate Majority Policy Committee listen to Rudy Giuliani speak, Wednesday, Nov. 25, 2020, in Gettysburg, Pa.

Dec. 7: State Supreme Court rejects Trump’s appeal of a decision pertaining to fewer than 2,000 ballots cast in Philadelphia.

Dec. 14: Pennsylvania electors affirm Biden as the winner. Trump supporters don’t show up to protest, but some from the state GOP have been pressuring Pa.’s congressional delegation to dispute the results Jan. 6.

Meanwhile, at least 21 Pa. election officials quit during what they say was the most stressful, expensive election year ever, according to this Spotlight PA story.

Dec. 20: Trump appeals to SCOTUS to overturn three Pa. state Supreme Court decisions and the election results, and allow the state legislature to pick the winner.

Dec. 31: Seven Republicans in Pa.’s congressional delegation sign a statement that stops just short of committing to dispute results Jan. 6.

Jan. 4: Republican state Senators sign a letter urging Congress to set aside Pennsylvania’s electoral votes until after SCOTUS deals with a lawsuit that wouldn’t affect 2020 election results.

Jan. 5: The state Senate GOP refuses to seat Jim Brewster (D-Allegheny) because, although the state certified his election, Republican challenger Nicole Ziccarelli is still fighting the outcome.

U.S. Rep.’s Mike Kelly (R-16), Glenn Thompson (R-15), Guy Reschenthaler (R014) Fred Keller (R-12), John Joyce (R-13), Lloyd Smucker (R-10), Scott Perry (R-10) and Dan Meuser (R-9) (all but one of nine Pa.’s Republican Congressmen) definitively and publicly commit to contesting the commonwealth’s electoral votes just before Congress convenes Jan. 6.

Sometimes, your mornings are just too busy to catch the news beyond a headline or two. Don’t worry. The Morning Agenda has got your back. Each weekday morning, host Tim Lambert will keep you informed, amused, enlightened and up-to-date on what’s happening in central Pennsylvania and the rest of this great commonwealth.

The days of journalism’s one-way street of simply producing stories for the public have long been over. Now, it’s time to find better ways to interact with you and ensure we meet your high standards of what a credible media organization should be.