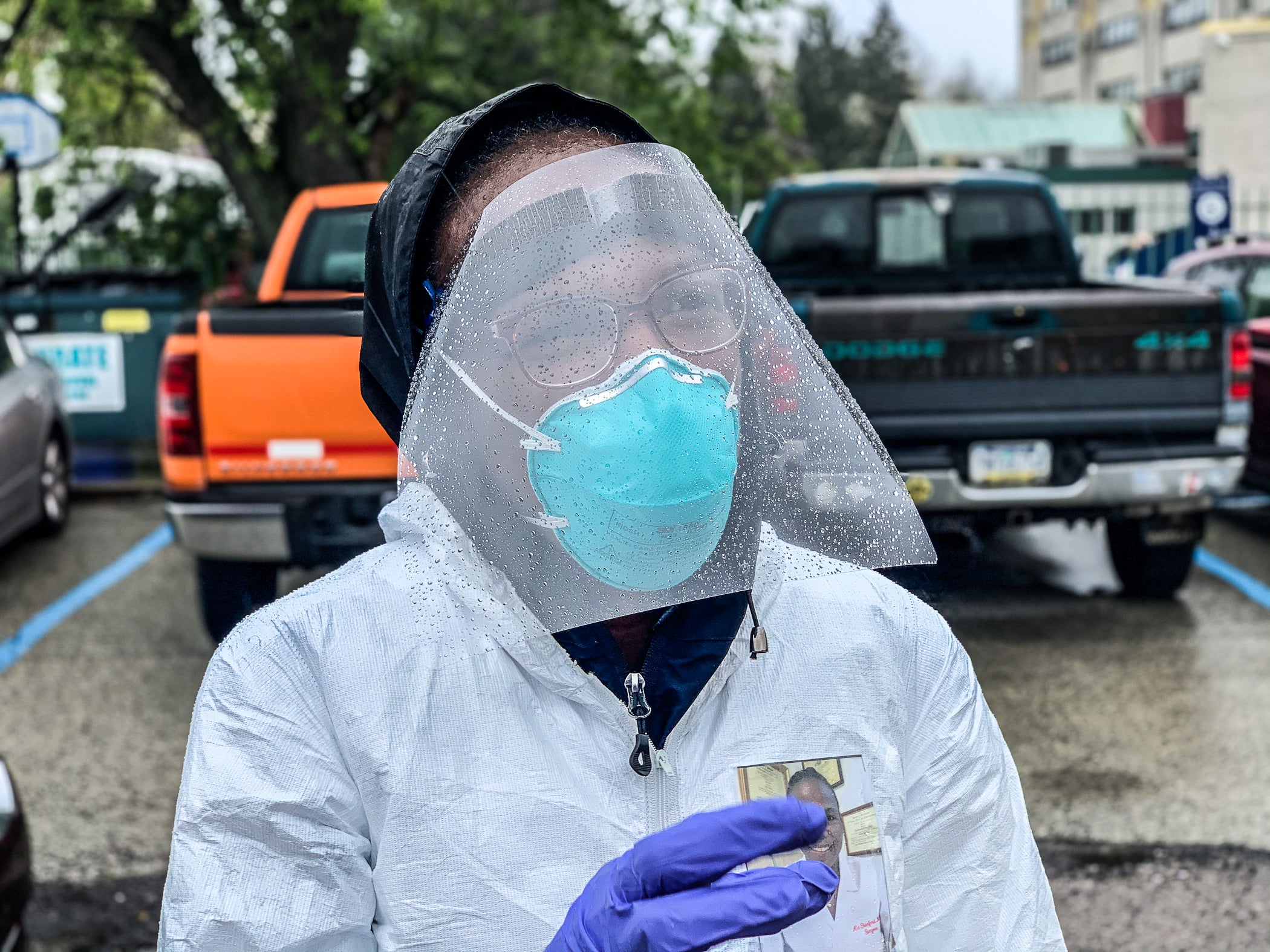

A Black doctor performs a free COVID-19 test in the parking lot of the West Philadelphia Seventh-day Adventist Church. (Christopher Norris for WHYY)

A Black doctor performs a free COVID-19 test in the parking lot of the West Philadelphia Seventh-day Adventist Church. (Christopher Norris for WHYY)

A Black doctor performs a free COVID-19 test in the parking lot of the West Philadelphia Seventh-day Adventist Church. (Christopher Norris for WHYY)

What you should know

» Coronavirus facts & FAQ

» Day-by-day look at coronavirus disease cases in Pa.

» It’s time to get serious about social distancing. Here’s how.

(Philadelphia) — It was early last Friday morning when Andrea Lawful-Sanders, an on-air personality at WURD Radio, witnessed dozens of cars waiting to get into the parking lot of the Mt. Airy Church of God in Christ.

People were waiting at the 6401 Ogontz Ave. church for COVID-19 tests administered by the Black Doctors COVID19 Consortium, which had organized yet another one of its free-of-charge community testing events. Lawful-Sanders was there to drop off face masks.

Two days later, the collective of Black doctors and pastors were back at it, this time offering testing for the disease caused by novel coronavirus at the West Philadelphia Seventh-Day Adventist Church. The pastor there, Nick Taliaferro, was first in line to get tested.

“They stick a swab so far down your nose, it almost feels like an enema,” Pastor Taliaferro said with a chuckle. “It was totally uncomfortable.”

When Pastor Taliaferro arrived at his Haverford Avenue church that Sunday at 8:30am, an hour and a half before testing began, he saw cars stretched from the parking lot gate on 46th street, down to nearly 44th street.

By 11:45am, about 100 people had been tested. It’s a scene that’s been replicated at Black churches across Philly.

“When times get dark, the church demonstrates its relevance. What you’re seeing now is the church, as it has always been in the Black community in particular, filling the place where government and social-economics fail,” Pastor Taliaferro said.

These churches have anchored the newly formed consortium’s efforts, making available their parking lots to test residents in underserved communities.

Miller Memorial Baptist Church in North Philly served as the launching pad for the urgent movement, led by pediatric surgeon Ala Stanford. Stanford, who has a private practice in Jenkintown and is also on staff at Abington-Jefferson Health, started testing people at the church on April 18, just as news of the coronavirus’ toll in the Black community began coming out.

Enon Tabernacle Baptist Church in Germantown hosted the outdoor effort two days later.

Dr. Stanford attends the historic Salem Baptist Church, where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. famously preached a sermon in 1963. The church last year relocated to Roslyn from Jenkintown. The Rev. Marshall Mitchell of Salem Baptist said he and the doctor, who are friends, have talked about the health disparities among African Americans for years. When the coronavirus outbreak occurred, the two talked again on the subject and decided to act.

Dr. Ala Stanford is a member of the historic Salem Baptist Church, which in 2019 moved from Jenkintown to Roslyn. (Christopher Norris for WHYY)

“Hundreds of churches have reached out to us, but I have to scout locations to make sure the churches have large parking lots,” said Rev. Mitchell. “One thing that makes these churches different from public school and supermarket parking lots is that these are all locations owned by Black people.”

Salem Baptist Church, located in a suburb where the population is less than 20,000, hasn’t hosted any testing. Nor are there any plans to do so. Rev. Mitchell said the team is “focused on where the disease” is and where help is most needed. And at the moment, that’s Philadelphia.

Carla Clarkson – a minister, hairstylist and member of Salem Baptist Church – was among the people on Sunday who volunteered in West Philadelphia. Clarkson, who told WHYY that she had been experiencing some flu-like symptoms, also got tested. She then revealed that two of her mentors – black women – had tested positive weeks ago, but both have since recovered.

African-Americans are disproportionately impacted by the coronavirus, which to date has infected close to a million people in the United States; more than 55,000 of those cases proved fatal.

Of the total number of COVID-19 cases, 30% are Africans-American, according to the latest data from The Center for Disease Control. And the Associated Press reported that roughly a third of the U.S. COVID-19 fatalities are African American.

Though the racial data for the city and state is incomplete, the latest statistics show that African Americans make up 45% of the total confirmed COVID-19 cases in Philadelphia, and 10% of total cases in Pennsylvania. Black people make up just 12% of the state’s population. More than half of the Philadelphians killed by COVID-19 were African American, according to city data.

“I know 35 people who have died from coronavirus,” said Rev. Mitchell. “None of them were white.”

Americans with premorbities, such as obesity, high blood pressure and type 2 diabetes, are at a higher risk for contracting the coronavirus. However, these underlying conditions are more prevalent in Black communities.

Dr. Stanford told WHYY earlier this month that less access to health insurance, coupled with the fact that a big portion of Philadelphia’s working class, public-facing jobs are performed by African Americans, contribute to the disparity. That said, COVID-19 doesn’t discriminate between an individual with premorbities and another without.

“The coronavirus doesn’t care about your pulpit, purse, or power,” said Rev. Mitchell, who tested negative for COVID-19.

On April 23rd, Rev. Alyn E. Waller, pastor of the over 15,000-member Enon Tabernacle Baptist Church, revealed that he tested positive for the coronavirus. Though not showing symptoms, Rev. Waller chose to get swabbed at a consortium testing event at Enon on April 20 to model behavior and emphasize the importance of testing. A photo in The Philadelphia Tribune shows Rev. Mitchell and Rev. Waller elbow bumping each other during that event. Rev Waller has no known pre-existing conditions.

“I applaud Pastor Waller because he made himself vulnerable. And one of the proudest traditions in the Black church is to make yourself vulnerable,” said Rev. Mitchell.

Rev. Malcolm Byrd, former director of the Mayor’s Office of Faith Based Initiatives, said Rev. Waller is courageous for both taking the test and disclosing his results. “It’s characteristic of him to accept the burden of leadership that says: ‘If I ask you to do it, I need to do it as well.’ ”

In a Facebook live broadcast, Rev. Waller said he hopes people will learn from his experience and “stay in unless you absolutely have to go out.” Pennsylvania’s stay-at home order is in effect until May 8th.

Upon learning of Rev. Waller’s diagnosis, a couple of pastors, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, questioned whether the church was taking unnecessary risks by aiding the free testing. Pastors should leave the testing to the medical professionals, they said. But most local faith leaders and congregants overwhelmingly affirmed support of Black churches aiding doctors in testing for COVID-19. In fact, a prevailing sentiment was that the Black church has never been more relevant and required.

“The hospitals are overwhelmed and, if there’s a possibility that pastors can step up and assist the doctors, they should. The church is not just there for us to just lift holy hands,” said Lawful-Sanders.

Rev. Mitchell questioned: How could the church, and its leaders, not put itself at risk for the benefit of its people?

“This is a moment of crisis that could very well save the Black church in the mind of people everywhere, but only if the church understands the power of this moment,” said Rev. Mitchell.

Rev. Byrd – whose nonprofit organization has donated $2,000 to the consortium’s GoFundMe account – said it’s “most responsible for the pastors, who have the means to facilitate testing, to bridge the gap between the public health infrastructure and the community.”

As of April 27, the Black Doctors COVID-19 consortium has raised $89,928 of their stated goal of $100,000. According to Rev. Mitchell, each day of testing costs between $30,000 to $40,000. On average, roughly 300 people are tested per site, both Rev. Mitchell and Pastor Taliaferro confirmed. Monies donated are largely used to pay for tests; the doctors, pastors and laypeople are volunteering 100 percent of their time.

The idea of Philadelphia’s Black Christian leaders stepping up to assist doctors during a seemingly unprecedented health crisis may seem novel. After all, we’ve never seen anything like this COVID-19 pandemic, right? Wrong.

In 1793, Philadelphia experienced a Yellow Fever outbreak, which at the time was said to be the worst pandemic ever recorded in North America. More than 5,000 Philadelphians died of Yellow Fever, of which roughly 400 of the deceased were African-American. Dr. Benjamin Rush – a Philadelphia physician, civic leader and signer of the Declaration of Independence – initially believed that African Americans were immune to the disease. He later realized his mistake, but by that time, Yellow Fever had spread to New York. That year, the doctor urged Richard Allen and Absalom Jones – the first two African-Americans to receive formal ordination in any denomination – to step in and help the sick. They obliged, as did other members of the African-American community, be they clergy or otherwise.

In 1794, 10 months after the epidemic, Allen founded the Mother Bethel A.M.E Church, which holds the title of the oldest African Methodist Episcopal congregation in the United States. Mother Bethel’s current pastor, the Rev. Mark Kelly Tyler, recently raised the story of Yellow Fever with the congregation.

“My main teaching point,” he said, “is that when the epidemic hit in 1793, Richard Allen was leading his people as a congregation. Although they had no church building, they were the church. They served the community; they risked their lives as nurses; they buried the dead; they served in a heroic fashion to save the city of Philadelphia; and they continued to stay together.”

Mother Bethel isn’t currently involved in any community testing for COVID-19. However, the church has joined an effort from P.O.W.E.R, a local interfaith coalition, to decarcerate the overcrowded city and state jails. The City of Philadelphia has begun to facilitate the release of inmates, although the names are kept private.

On April 22nd, the ACLU published the results of their first-of-its kinds epidemiological model, which showed that “as many as 200,000 people could die from COVID-19 – double the government estimate – if we continue to ignore incarcerated people in our public health response.”

“This is the perfect time for the church to step up,” said Rev. Tyler, who has recruited 50 congregants to do weekly calls to the other 700 members of Mother Bethel and inquire of their needs.

But what else can leaders of the Black churches do in this moment?

Rev. Tyler and others suggested that, amid the pandemic, pastors can play the role of fact-checkers, filtering the true and relevant information communities need to survive, from the rumors, hyperbole and bizarre recommendations which pose a threat to public safety.

“We should be reinforcing the positive messages from the CDC, Dr. [Anthony] Fauci and others when appropriate,” said Rev. Tyler, who warned his congregation against shaking hands on the second Sunday of March.

Agreeing with Rev. Tyler, Rev. Juwan Bennett, the 27-year-old co-pastor of New Life Baptist Church in Germantown, said the best thing he and other faith leaders can do is combat misinformation.

“The information is changing so quickly. We have to be vigilant, and keep our members informed.”

Whether it be food giveaways – which local churches have done for years in Philadelphia prior to the pandemic – free COVID-19 testing, fact-checking crucial information or offering messages of hope to the sick, scared, and grieving, the Black church is busy, even if its pews are empty.

Rev. Bennett lives a stone’s throw away from the People’s Baptist Church on the 5000 block of Baltimore Avenue in West Philadelphia. On Wednesdays from 9:30-11:30a, that church, led by Rev. Eric Goode, is giving away food. On average, Rev. Goode says they feed 50 people a week.

Rev. Bennett’s wife has been calling many of the older members of their church to do a needs assessment and help them navigate the hyperflow of information. Rev. Byrd said that because of frequent life-and-death misinformation from the White House, “church leaders must vet information and then share with it those who trust us.”

“Quite frankly, historically, that has always been the role of the black church,” said Rev. Byrd. “Have we been relaxed in recent generations? Perhaps. But this presidency, over the last several years, has energized us and reminded us that we’re not just to share God’s truth, but reality-test any so-called truth that’s presented to us. If not us, then who?”

WHYY is the leading public media station serving the Philadelphia region, including Delaware, South Jersey and Pennsylvania. This story originally appeared on WHYY.org.

Get insights into WITF’s newsroom and an invitation to join in the pursuit of trustworthy journalism.

The days of journalism’s one-way street of simply producing stories for the public have long been over. Now, it’s time to find better ways to interact with you and ensure we meet your high standards of what a credible media organization should be.