A small creek runs through the Shirk family farm in Caenarvon Township, Lancaster County on Wednesday, Jan. 8. 2020.

Rachel McDevitt / WITF

A small creek runs through the Shirk family farm in Caenarvon Township, Lancaster County on Wednesday, Jan. 8. 2020.

Rachel McDevitt / WITF

Rachel McDevitt / WITF

A small creek runs through the Shirk family farm in Caenarvon Township, Lancaster County on Wednesday, Jan. 8. 2020.

(Harrisburg) — Hundreds of high school students, all wearing blue corduroy jackets, packed the main arena at this year’s Pennsylvania Farm Show.

State officers for the Pennsylvania Future Farmers of America danced onstage to Dolly Parton’s “9 to 5” in between introducing guests of honor and announcing various awards for the organization’s members.

The club’s mid-winter convention celebrated the overall theme of the Farm Show: Imagine the Opportunities.

Rachel McDevitt / WITF

Members of the Pennsylvania Future Farmers of America gather for the organization’s Mid-winter Convention at the Farm Show Complex in Harrisburg on Monday, Jan. 6, 2020.

But while this wave of blue appears to represent the next generation of growers, ranchers and producers, not all FFA members are “future farmers.” They might become researchers, business owners or teachers — related jobs that agriculture boosters say will be needed as the industry tries to feed a growing population. The Earth is expected to add another two billion people by the year 2050.

Pennsylvania is a major grower of produce such as mushrooms, apples and peppers, as well as a big producer of eggs and dairy products.

But to keep that status, the commonwealth will need to find answers to the who and where of future farming.

“It is something that is ever-present, this issue of transition,” said state Agriculture Secretary Russell Redding.

Agriculture accounts for 18 percent of the state’s economy, but it faces serious challenges.

One is aging farmers. Pennsylvania has twice as many farmers over 65 than under 35, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s latest census.

FFA members could make up some of that difference.

But those who go into production agriculture will have to find land to work on, and that’s another challenge, because Pennsylvania is losing farmland.

The USDA’s 2017 Census of Agriculture shows more than 400,000 acres went out of production in the state since 2012, about 5 percent of all farmland in the commonwealth.

Finding land can be especially hard for young farmers who don’t come from farming families.

Pennsylvania has some of the country’s more expensive farmland. In 2018, the USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service found farm real estate values in the state rose 1.6 percent from the previous year to average $5,600 an acre.

Tyler Shaw, a Dauphin County hay farmer, said it’s more cost-effective for farmers to rent farmland than to own it.

Rachel McDevitt / WITF

Tyler Shaw stands outside a log cabin at Blue Mountain Farm on Thursday, Jan. 2, 2020.

The 23-year-old originally got interested in agriculture through 4-H, and helped his family turn their wooded lot into Blue Mountain Farm. They raise a few animals — Angora goats at the moment — and run a fiber mill.

Shaw started renting more ground when he was in high school. At first, he was just trying to grow enough hay to feed his own animals. He expanded it into a business, and by the time he was 16, he had 15 landlords.

He now rents about 350 acres from 25 landlords. And he’s hoping to buy a small farm of his own in the next few months.

Shaw said access to land is probably the biggest barrier a young farmer faces.

“Land isn’t something you can just go to the store and buy,” he said. “You can’t go to the farm sale down the road this Saturday and, you know, purchase a lease agreement. That’s not how it works.”

He said getting farmland takes relationships, time and money.

Shaw hopes to take advantage of a new tax credit passed by the state legislature last year that will give an incentive to landowners to sell or rent farmland to young farmers — those who have been at it for less than 10 years.

He said the credit will hopefully give young farmers an advantage over real estate developers in acquiring farmland.

Midstate counties with some of the most productive farmland in the state are also seeing some of the fastest population growth, according to estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau. Cumberland and Lancaster counties are both seeing increased development.

Some farmers might be tempted to sell their land to developers, but others don’t want to see their land be used for apartment buildings or shopping centers. Some are turning to farmland preservation.

Through nonprofits or government programs, farmers can get an easement on their land to restrict all future use of the property to agriculture.

Preservation is one answer to the question of where people will be able to farm, but it’s not fully stopping the loss of farmland.

Even Lancaster County — one of the top counties for preserved farmland nationally — has been losing about 1,200 acres annually for several years, according to USDA data.

While demand for farmland in the county is strong thanks to a large population of Amish and Mennonite residents, it’s also facing pressure from development.

“It’s sort of a catch-22 because Lancaster’s such a great place that a lot of people want to live here, but they need land to live on. And we’re consuming that productive land, which is growing houses, in some cases, rather than the agricultural products that it could be,” said Jeff Swinehart, chief operating officer for Lancaster Farmland Trust.

Swinehart said the trust has seen interest in preservation grow recently. Fifty farms are on its waiting list.

He noted the county is well situated for agriculture: the land is productive, and it has the right infrastructure and proximity to large metropolitan areas to easily get products to market.

“So, it would make sense that if we’re going to protect land, we might as well protect it here,” Swinehart said.

Reasons to preserve farms range from the practical to the personal.

Paula Shirk preserved her family’s 56-acre farm in Caernarvon Township through the trust last year, in memory of her late husband.

Rachel McDevitt / WITF

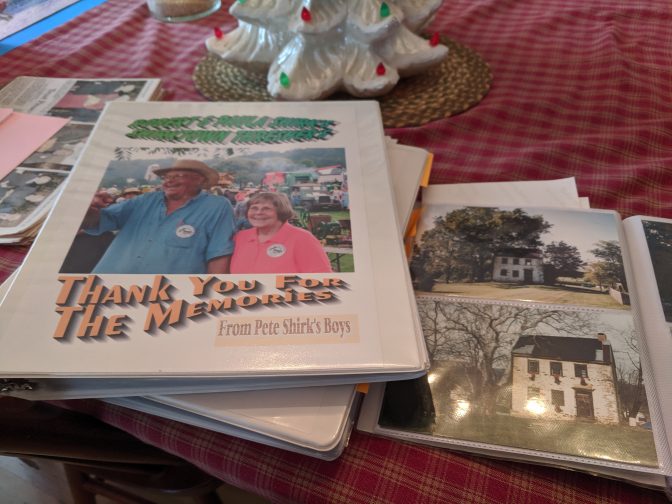

Photo albums sit on the dining room table in the Shirk family’s farmhouse. The farm has been in the family since 1792.

She easily found a tenant to work the farm. Leallen Newswanger grew up across the road. He said if this land wasn’t available to rent, he’d probably be looking for a place to buy out of state, because farms in Lancaster County are so expensive.

Shirk said she’s noticed development creeping in from nearby Morgantown. Her daughter, Beth, said they can now see the glow of Walmart’s lights peeking over the hills.

After her husband Robert’s death in 2017, Shirk said she felt compelled to preserve the farm for him.

She also wanted to honor his family’s history. They’ve been on the land since 1792.

“It’s like my gift to future generations,” she said. “This is what we had in our life that we enjoyed, and we were blessed to be here.”

Sometimes, your mornings are just too busy to catch the news beyond a headline or two. Don’t worry. The Morning Agenda has got your back. Each weekday morning, host Tim Lambert will keep you informed, amused, enlightened and up-to-date on what’s happening in central Pennsylvania and the rest of this great commonwealth.

The days of journalism’s one-way street of simply producing stories for the public have long been over. Now, it’s time to find better ways to interact with you and ensure we meet your high standards of what a credible media organization should be.